|

|

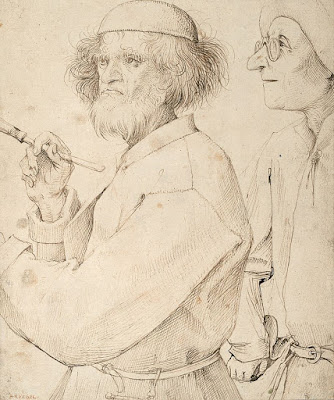

Moonlight, c. 1883-1889, Ralph Albert Blakelock, courtesy of the High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia

|

With the time change, the rhythms of the night are all wrong. Between that, the full moon, and the low-pressure system that is bearing down on us, I’ve spent too many hours up during the long reaches of the night.

Whenever I watch moonlight, I think of

Ralph Albert Blakelock, the most famous painter you never heard of. In 1916 he managed to set a record for the highest price paid for a painting by a living American artist ($20,000). Sadly, he was in an insane asylum at the time.

Blakelock was born on Christopher Street in what is now Greenwich Village, in 1847. He was just too young to have served in the American Civil War, at that impressionable age of boyhood where war is glorious and terrifying.

He started studies at what is now City College of New York, intending to be a homoeopathist like his father. After three terms, he dropped out.

|

|

Moonlight, c. 1885-1889, Ralph Albert Blakelock, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

|

After the Civil War, many artists traveled through the American west under the auspices of the Federal government or trading companies. From 1869-72, Blakelock did a similar thing, but as a free agent. Traveling alone in the west at that time was a very dangerous matter. Blakelock lived among the Sioux for a time, traveled down the California coast to Mexico, and returned to New York via a fruit boat from Panama.

Almost completely self-taught, he began producing landscapes and scenes of Indian life based on his notes and sketches. His work was recognized and lauded, and he produced a show at the

National Academy of Design. In 1877, Blakelock married; he and his wife had nine kids.

|

|

Moonlight, Indian Encampment, 1885-1889, Ralph Albert Blakelock, courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

|

Blakelock may have been a great painter, but he was a financial incompetent and plagued by doubts about the worth of his work. He was simply unable to establish any kind of business to support his family. Profoundly depressed, he began to show signs of mental breakdown. Meanwhile, his wife and children lived in acute financial hardship, which was amplified by the Depression of 1893.

Blakelock suffered his first complete breakdown in 1891. For eight years he suffered from schizophrenic delusions until he was committed to the

Middletown State Homeopathic Hospital in Orange County, New York. At the time, that was the backwoods. He would live there almost until his death.

And that’s where his story went from tragic to sordid. The 19th century romanticized mental illness. Rich people visited asylums for fun, watching the antics of inmates with great interest, or inviting them to be entertainment at their parties. Newspapers printed stories of the odd adventures of lunatics. Blakelock, with his quirks, his odd way of painting, and his weird behavior, was perfect fodder for this cruel mania.

Enter the swindler, in the form of one Beatrice Van Rensselaer Adams, née Sadie Filbert. Her questionable charities were outweighed by her political and social credentials. Blakelock was a perfect lamb to be led to slaughter. Adams established the Blakelock Fund to support his family, but of course, its purpose was to enrich her.

|

|

Moonlight, 1885-1889, Ralph Albert Blakelock, courtesy of the Corcoran Museum. Are you detecting a theme here?

|

Harrison Smith, a reporter for the New York Tribune eventually convinced Blakelock’s keepers that he was, in fact, a famous artist with work in a major retrospective in the city. When taken to New York to see the show, Blakelock confided to Smith that several of the paintings on exhibit were forgeries. Since the man was a diagnosed lunatic, however, Smith kept this information under his hat.

At the time of his death on August 9, 1919, Blakelock was hailed by the London Times as “one of the greatest of American artists.”

Blakelock painted in the style we now call

tonalism. Popular between 1880 and 1915, it emphasized mood, myth and spirituality, in landscapes that were rendered in dark, neutral tones. Tonalism was in part an emotional reaction to the profound, heartbreaking damage of the Civil War. It was the perfect métier for a fragile, broken man.