Only got an hour? If you’re set up right, you can still do a credible field painting.

|

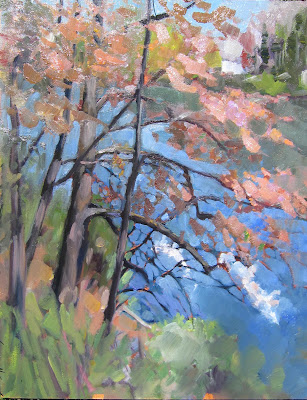

| The bones of a painting. |

I

mentioned last week that I didn’t have time to get back to paint the apple tree at the

abuelitos’ house in the tiny

pueblo above Pecos, NM. That tree is what initially drew me to the place, and I didn’t want to leave without painting it. On Friday morning I went back to the little village to make a quick sketch. I was carrying only 12X16 canvases, so I had to work very fast.

I had two hours before I needed to get back to the ranch and pack for my flight. It turns out I had less time than that, because it spattered rain. But I was still able to get a field sketch done.

|

| You’d hardly want to paint from this photograph, unless you knew what a magical place it was in real life. |

I seldom paint from photos without a good field sketch alongside. One glance at my photograph will tell you why. Camera lenses distort shapes and flatten color and light. I know how to use my camera to make more interesting photos, but I eschew that artistry in reference pictures. Photographic artistry comes at the expense of details and architecture I want to preserve for the expression of the painting.

A good photograph is not necessarily a good reference photograph for painting. For example, too tight a crop often leaves out details you need later. Artists constantly move things around when painting, and you can’t do that if you’ve cut those items out.

|

| The paint array never changes, no matter how fast I’m painting. (The bottle cap is there for medium.) |

Start by putting out your typical array of colors, including a dark mix with which you will draw. In the northeast, I typically use a dark mix of ultramarine and burnt sienna. In New Mexico, I made a mix of ultramarine and quinacridone red. I thought I was pushing the purples excessively, but in comparison with other paintings at the opening, my work felt low-key. That’s less a question of the light than of regional tastes.

Note the line of white just below my pure pigments. I always make tints of my colors when I start. That too speeds up my painting.

I do not clean my palette except for before a flight or at the end of the season. It goes in the freezer in a waterproof stuff-sack. That means I don’t have to mess around putting out paints at the start of each painting session. That’s important, since setting them out and cleaning them up can use up a half hour of precious time.

|

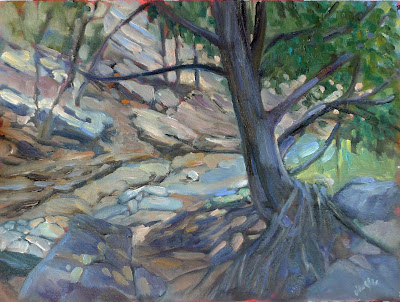

| A very sophisticated drawing, the work of about two minutes. |

Fast painting is where the habit of always setting out your paint in the same order helps. It would be disconcerting for a musician to find the keys of the piano in different places each time he played, or for a surgeon to have to hunt for the proper scalpel. The same is true in paints. You can read about my color organization

here, but the important thing is consistency.

I did not do a value study for this super-fast painting. I simply outlined my drawing with large strokes. Then I filled in the drawing with blotches of color. Mix and splat, with a fairly heavy dilution with mineral spirits.

From there, it was just a question of revising and dividing shapes. I was starting to break the apple tree into a pattern when the rain kicked up.

|

| Right before scraping back and packing up. |

My last step, which I forgot to photograph, was to scrape back slightly—not to bare canvas, but so I have a level surface on which to proceed. It’s important to not leave impasto in a half-finished alla prima painting, especially when you don’t know when you’ll get back to it. Scraping back often reveals the true lines, since it creates a shadow average of all your guesses in different layers.

And then I ran for the car. No, I didn’t win any prizes, but I don’t think my choices of paintings had anything to do with that. There was some terrifically strong work in this show. Onwards and upwards!