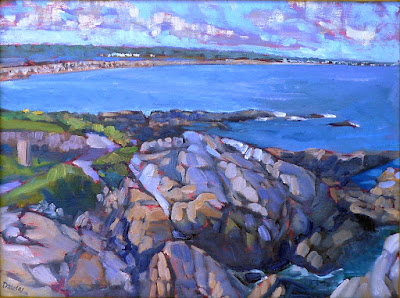

Bravura brushwork rests on a foundation of practice and skill.

|

|

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, Vincent Van Gogh, courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

|

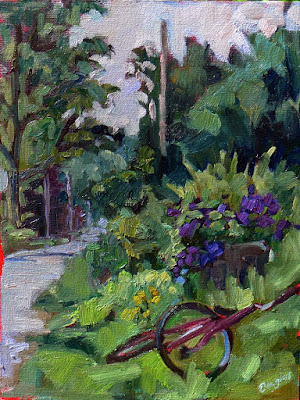

“Painterly” describes a painting that is comfortable in its own skin. It uses the paint itself to create movement and expression. It’s a quality found in every medium; even sculpture is sometimes described as painterly. Painterly works are loose and emotive, and they lead with their brushwork.

This is a sensual, rather than intellectual, quality. It comes from experiencing the paint itself. You’re there when you no longer fight the paint, but work with it. It’s the opposite of photorealism, where the artist works hard to conceal all evidence of his process. A painterly painting doesn’t fuss over the details.

Does that mean it must be impasto? No.

Peter Paul Rubens,

JMW Turner and

Joaquín Sorolla were all painterly painters, and none of them wallowed in paint. There are many fine contemporary painters who work thin and expressively.

|

|

Cloud study, watercolor over graphite, 1830–35, John Constable, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. We don’t usually think of Constable as painterly, but he was in his plein air work.

|

The term “painterly” was coined in the 20th century by art historian

Heinrich Wölfflin. He was trying to create an objective system for classifying styles of art in an age of raging

Expressionism. The opposite of painterly, he felt, was “linear,” by which he meant paintings that relied on the illusion of three-dimensional space. To him this meant using skillful drawing, shading, and carefully-thought-out color. Linear was academic, and painterly meant impulsive.

Today, we don’t see accurate drawing as an impediment to expression. In plein air work, acute drawing is often overlaid with expressive brushwork. The idea of painterliness—of being loose and self-assured—is treasured even as we strive for accuracy.

|

|

House in Rueil, 1882, Édouard Manet, courtesy National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

|

How do we develop painterliness?

First, master the fundamentals. “You can practice shooting eight hours a day, but if your technique is wrong, then all you become is very good at shooting the wrong way,” said basketball great

Michael Jordan. “Get the fundamentals down and the level of everything you do will rise,” he said. That’s very true of painting, where there is a specific protocol for putting paint down.

Then practice, practice, practice. “I’m not out there sweating for three hours every day just to find out what it feels like to sweat,” said Jordan.

Expect failure. It comes with pushing your technique. “I have missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I have lost almost 300 games,” said Jordan. “On 26 occasions I have been entrusted to take the game winning shot… and missed. And I have failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

|

|

Beach at Valencia, 1908, Joaquín Sorolla, courtesy Christie’s

|

You can’t teach yourself to be relaxed; you can only get there through experience. The only way to be painterly is to paint. I can show you expressive brushwork techniques, but there are still no shortcuts. It happens automatically and naturally with experience. You stop focusing on the mechanics, and start focusing on what you see. Your eye is on the ball.

Many times, artists only realize their painterly styles in old age. That is when

Titianstarted painting in blotches, in a style that came to be known as

spezzatura, or fragmenting. “They cannot be looked at up close but from a distance they appear perfect,”

wrotethe Renaissance art critic

Giorgio Vasari. Rembrandt is another painter who started out painting precisely but ended up loose.

Édouard Manet is still another. In fact, the list is inexhaustible.

Vincent Van Gogh is the personification of painterliness. He died at 37, but still managed to produce around a thousand paintings (that we know of).

Bravura brushwork simply rests on the foundation of all those paintings that went before.