The best way to learn about your brushes is to experiment.Your brushwork contributes immeasurably to the quality of your painting. Don’t dab or be diffident; plan your strategy and then execute it with boldness.

|

| A spalter or mottler is a most useful watercolor brush. |

On Friday, I gave you a guide to buying brushes. What are you going to do with these brushes now?

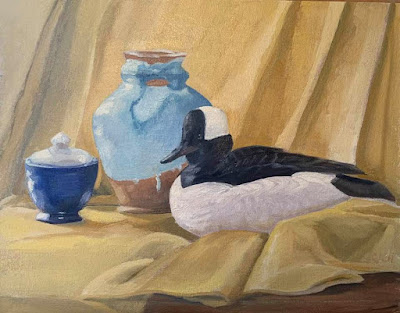

OIL and ACRYLIC

In the following illustrations, I’ve tried to keep the amount of solvent the same (except with the fan brush).

Above is a sable flat brush by Rosemary & Company. It can put down a very smooth surface and offers a lot of control, but it doesn’t carry the quantity of paint that an equivalent bristle brush will. I save sable for glazing or blending.

This is a hog bristle flat brush. The paint it lays down is both rougher and more impasto than the sable.

Flat brushes make an immediate, energetic mark. They’re excellent for fast, powerful surface work, long sweeping strokes, and blocking in shapes.

Used on their sides, they also make great lines, far more evenly than a small round can do.

Two rounds of very different sizes. A round is a more lyrical brush than a flat, and is a classic tool for painterly surface marks. It can be used to make lines that vary from thin to thick. A pointed round is used for fine detail. Bristle rounds tend to lose their points very quickly, however.

The great advantage of a filbert is the variety of brushstrokes you can get from one brush. This is great for single strokes that taper, such as in water reflections. Its rounded edges are good for blending. Set on its side, it makes nearly as good a line as a flat.

A bright is a less-flexible version of a flat. It’s great for short, powerful strokes or situations where you want a lot of control.

A fan brush probably has no place in a plein air kit, but I carry one anyway. I use it for blending, as on the left, although some people like using it to make whacked out marks as on the right. The problem is, it can carry very little paint, so its marks tend to be either gooey, as above, or very abrupt.

In my studio, I just use a clapped out soft-haired brush to blend.

Many plein air painters also carry liners and riggers, which are useful in paintings that are built up smoothly. I don’t paint that way, so I seldom use them. Another brush that is good for detailed work is an angled brush. I don’t have one of them, either. You can do almost any work you can envision with just the brushes I’ve shown you above.

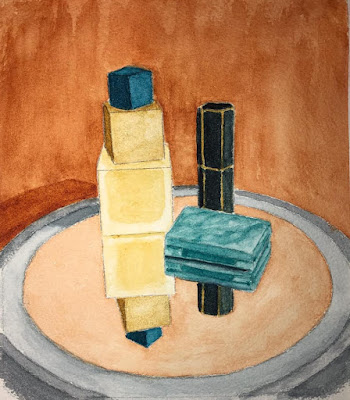

WATERCOLOR

Watercolor brushes are softer than oil-painting brushes. The most expensive are natural bristles, and the difference is usually worth paying for. Natural bristles combine strength with suppleness and hold more paint than synthetics. Unlike oil-painting brushes, your watercolor brushes should last a lifetime, so buy the best you can afford.

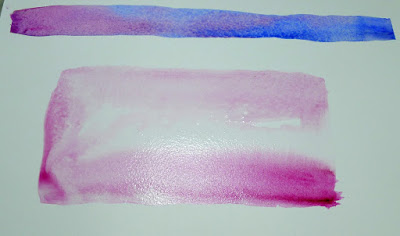

In general, watercolor brushes drop more pigment the more vertically they’re held. You can use this to move from a filled area to a broken one in one brush stroke. In all the following examples except for the mop, I’ve held the brush both ways. A good general rule is to carry the vertical brush slowly and in a controlled manner; pull a horizontal brush more rapidly to get the least amount of paint contact with the paper.

|

| Made with the spalter brush at the very top of the page. |

The brush I used for the photo montage at the top of the page is a 2″ flat synthetic mottler or spalter brush. I like this shape for both oils and watercolor. It’s a relatively inexpensive brush that gives a beautiful wash. It’s useful for covering large areas quickly, but with precise edges.

|

| A flat gives you good even washes. Used on its side, it can give you a controlled line. |

|

| A bright is a shorter version of a flat. More punch with less pigment. |

Flats and brights give you nice flat washes, but can be used to make expressive lines as well. Brights have more control and carry less paint, just as they do in oil painting. Turn them on their sides to make a controlled line. Twisting the brush while painting gives an infinite variety of shapes. So too does varying the ratio of paint and water.

|

| You can’t do either of these things in any other medium. |

Because of the way watercolor bleeds, its brushes can be used in ways not possible in any other medium–a long blend of different pigments, or by painting a shape in clear water and then dropping pigment into it.

|

| Round brushes give more lyrical lines than flats do. |

I don’t normally carry riggers with me in either watercolor or oils. (They’re meant to paint perfect lines, and my world-view apparently doesn’t have many perfect lines in it.) Most of my line work is done with rounds. They do not give as much control on long lines, but they are very expressive.

|

| A mop brush gives a perfect wash, but it does so much more as well. |

Squirrel mops are the most uniform wash brush you can use. It’s virtually impossible to make them skip, so use them where a lovely flat wash is a goal. But a good mop can also point, hold vast amounts of paint and sweep across the paper in style.

|

| I think Guillo the dog ate my sea sponge. |

Natural sea sponges are multi-purpose painting brushes. Use them to apply or remove paint. They can be as subtle or bold as you wish.