James Gurney somehow unearthed a 1942 copy of American Artist Magazine that included an interview with a young Andrew Wyeth on his technique. Wyeth, in his later years, became schtum about method and his estate is highly restrictive about images. As a teacher, this is frustrating. Students could learn much from studying his method and work, even if they have no interest in painting like him. He was one of the principal realist painters of mid-century American art.

This interview was done when Wyeth was a callow 25-year-old, before Christina’s World catapulted him into superstardom. At that age, he painted watercolor in quick wet washes, into which he dropped or drew off color as needed. “Wyeth’s practice is to skim off the white heat of his emotion and compress it into a half hour of inspired brush work. He is the first to admit the presumption of this kind of attack, and is ready to confess that it fails more often than it succeeds.”

That fast, emotional attack was the influence of abstract-expressionism, and a way to separate himself from his famous illustrator father, NC Wyeth. Even then, it was a far cry from Andrew's studio work, which was intentional, deliberate and labored. That was a function of his chosen medium. Egg tempera is transparent and thus suitable for working in glazes (indirect painting). Layers are laboriously built up, starting from a grisaille that gives definition to the whole.

Wyeth ultimately moved away from the pea-soup approach to watercolor, employing more dry brush and deliberation. That’s hard to see in the limited information available on the internet. I often suggest to students that they visit the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland specifically to look at Wyeth’s watercolors.

The Farnsworth has been as tight about sharing images as the Wyeth family themselves. But they have recently gotten better at putting their extensive collection online. You can find some gems there, including preparatory sketches for Wyeth’s paintings.

In that 1942 interview was the image at top, with the caption, “Wyeth often makes rapid ink sketches like this, on the spot, and then does the watercolor in his studio.” That’s the money shot right there, because Wyeth was employing a traditional technique of painters—creating a greyscale or notan sketch of the subject first.

Wyeth’s method ultimately involved lots of tinkering with the details in the form of sketches and alternate layups for his paintings. What I want my students to see is how much effort and thought he put in before he ever picked up his brush.

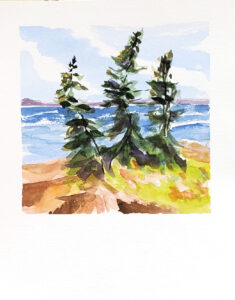

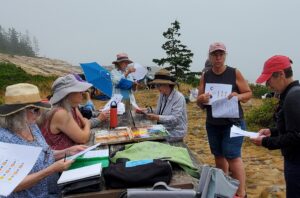

On Friday, I watched my workshop students’ kit while they went off to Corea Wharf for lunch. (There was no sacrifice there; I’m not a fan of lobster.) A small spruce, about two feet high, has audaciously laid claim to the top of a granite outcropping. It caught my eye. There can’t be more than a gallon or two of topsoil there. What there is, is poor.

I quickly drew a small sketch of these rocks with the idea of doing a painting later in my studio. Because Ken DeWaard’s voice was nattering in my head, I also took a reference photo. The sketch catches the curve that attracted my eye; the reference photo is completely anodyne. Nobody would choose to paint from it.

Perhaps at age 25 we are in touch with our internal frenzy to the point where we can say something useful without thinking too much, but there comes a time when our minds start to self-regulate. There are variations, but the process has traditionally been something along the lines of sketch-value study-final painting. Without that, we’re left with what Wyeth observed long ago—we fail more often than we succeed.