I’ll be teaching in the Adirondacks on August 13-14. Be there or be square.

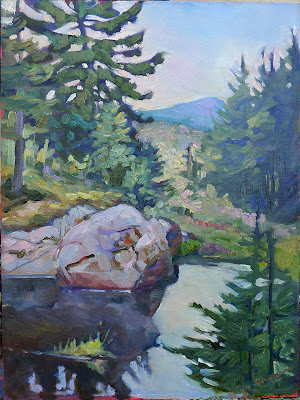

|

| Spruces and Pines in a Boreal Bog, painted at the Paul Smith’s VIC and long since gone to a private collector. |

I cut my teeth teaching workshops in the Adirondack wilderness, so it’s with great pleasure that I’ll be doing that again, August 13-14, at Paul Smiths College in the High Peaks region. (For more information see hereor contact Jane Davis.)

My Acadiaworkshop is sold out, so this is your only opportunity to study plein airwith me here in the northeast. It’s part of the Adirondack Plein Air Festival, but you do not have to be a participant in the festival to take the workshop.

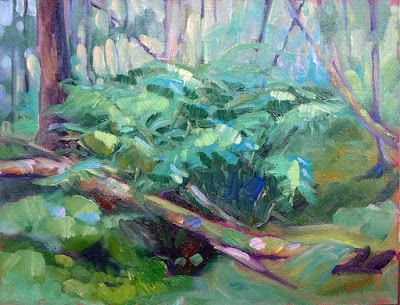

|

| Bracken fern, also painted at Paul Smith’s VIC. 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard, $869 in a plein air frame. |

(Of course, I have other workshops that still have openings—see my websitefor the full listing.)

New Yorkers are justly proud of the Adirondack Park. It covers most of the Adirondack Mountain massif and is the largest park in the Lower 48. Unlike most state parks, about half of the land is privately-owned, with state land wrapped around towns, villages and businesses.

I’ve been visiting the Adirondacks since I was a baby, and have painted, hiked, canoed and driven countless hours within it. But nobody can know the whole park intimately. It’s just too vast.

There are 6.1 million acres with more than 10,000 lakes and 30,000 miles of rivers and streams. There are boreal bogs and old growth forests, mountain peaks and roaring rivers. I’ve visited (and painted in) many wild places, and have found none wilder or more beautiful.

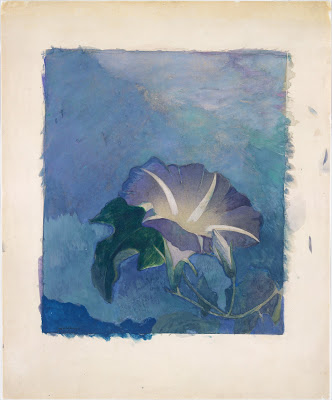

|

| The Dugs, painted in the Adirondacks near Speculator, NY. 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard, $869 in a plein air frame. |

As parks go, it’s pretty old. In 1885 the state legislature designated lands there and in the Catskills to be forever wild. This would come to be called ‘inside the blue line’. Those land protections were preserved in the state constitution in 1894. In contrast, the National Park System wasn’t formed until 1916.

There are about 130,000 full-time residents within the park and another 7-10 million visitors every year. That puts tremendous pressure on the land, but the relationship between residents, visitors, wilderness and government somehow holds together.

Because the park has so much private land within its borders, there are accommodations for every budget. You can stay at the newly-restored Hotel Saranac, or you can go back-country camping at a state-owned campsite. (The popular camping sites sell out fast, so don’t dither.)

|

| Whiteface makes its own weather, 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard, $869 in a plein air frame. Whiteface Mountain is one of the 46 High Peaks of the Adirondacks. |

My workshop will be held at the Visitors Interpretive Center (VIC) at Paul Smith’s College, which is located in the hamlet of Paul Smiths, NY. Town and college are named after Apollos (Paul) Smith, who started as a humble Vermont fishing guide and ended up an entrepreneur.

The VIC is an assortment of Adirondack habitats. There’s a large pond, running streams, a boreal bog, and lots of woodlands. Mountain peaks rise in the distance. Luxurious for a backwoods workshop, there are bathrooms with running water.

This teaching gig comes with the responsibility of being juror of awards for the Adirondack Plein Air Festival. Sandra Hildreth is the grande dame of Adirondack painting and the founder of the festival. She wanted a juror who was plugged into the ethos of wilderness and plein airpainting in general. These are two things I’m passionate about.

But my intimacy with the venue is also a potential downside—I know many of the painters who participate. Could I be objective? After a point, there are just too many of my acquaintances involved for me to favor anyone. I think I’ll be fine.