Don’t put your drawing in a box, put a box around your drawing.

|

| Painting a nocturne. |

There may once have been blueberries in abundance on Blueberry Hill. Now, it’s a parking loop above spectacular rock shelves and worn round cobbles, reaching down to an impossibly blue sea. The landscape is punctuated by beach roses, spruces, and jack pines.

Yesterday’s was an almost painfully clear light. Schoodic Island lies about three-quarters of a mile offshore. To have painted it in muted greys would have been an abject lie. There was little atmospheric perspective. Farther out to sea, the horizon was a pale, milky gold. Later in the day, of course, the wind rose and that all changed.

|

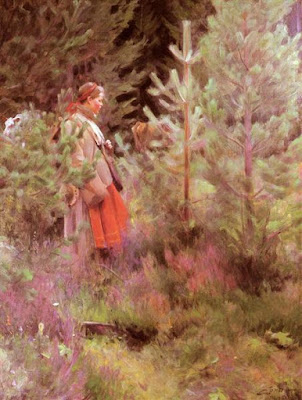

| Nancy’s never toned a canvas red before. She looks skeptical. |

I like to start my workshops by asking students to do a painting as they always do, without ‘orders’ from me. This is the only way I can see what they know. That works best with relatively experienced painters, and I’m lucky to have such a group this year.

That doesn’t mean I stay quiet. We only have a week together and I’m full of ideas. I start by making soft corrections. But I don’t yet start to dig into the matter of process.

|

| Beach painting, Maine style. |

One thing I’ve noticed recently is how many people start their sketches by drawing a box corresponding to the aspect ratio of their canvas. Then they draw a design inside of that box. To me, that’s backwards.

The drawing is the exploration process. We should start it without limitations, and let our fingers tell us what’s interesting. From there, we can crop the box shape around it, instead of the other way around.

|

| Becky’s hair tie. |

At lunch, I showed my students four or five ways to do a value study, none of which I currently use. Then I relented and showed them the method I do use. Of course, how it’s done isn’t important, just that it isdone.

I’m gently kicking the braces out of what has worked for them before. This is no place to leave people, so this morning I’m doing a long demo about my process. There’s nothing revolutionary about it: it’s cobbled together from teachers and painters who came before me. The goal is a fast, efficient alla prima technique that can deliver a finished painting in a few hours.

|

| This young lad was so taken by Fay’s painting, he thought she could sell it, “for maybe $85 or $90.” |

Meanwhile, I’d promised them the moon. A few minutes after seven we trundled down to the shore of Arey Cove. I’d guessed at three fundamental colors based on how the moon rose on Sunday night—a blue-violet shade, a clear blue shade, and a soft white tinted with yellow ochre.

A bald eagle flew along the shore just in front of us, low enough that we could see his tailfeathers. He perched nearby and stayed to watch the moon with us.

|

| Painting in Paradise. |

There was low-lying moisture on the eastern horizon. It looked for a while as if we wouldn’t have any moonrise at all. But suddenly, there she was, flickering behind the scant clouds. She rose steadily in the sky, a brilliant orange harvest moon, nothing like the pallid yellow orb of yesterday. We scrambled to adjust our color while she played peek-a-boo amid the clouds. Scratching from mosquito bites, we watched her slip behind a larger cloud. The eagle swooped into the gathering dark. It was done. We packed up.

As we walked back to our car, the sky cleared momentarily. The moon poured out a brilliant golden blessing of light to guide us home.