Technique is important, but it’s emotional power that draws people to paintings.

|

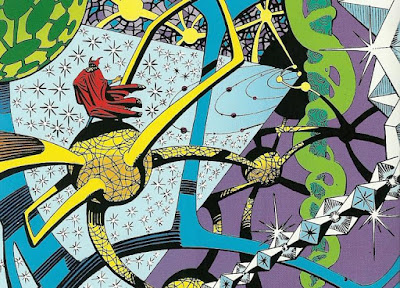

| Reading, by Carol L. Douglas. |

“I see artists who paint only flowers, only still life, only barns, only open landscapes, only portraits, only pets, only kitchen utensils, only books, only sailboats,” an artist said. “Why isn’t the artist painting more subjects, and trying new things?”

I’ve been painting long enough to have been there, done that. Some things I’ve tried simply don’t move me enough to focus on them. If I painted them, it would be only for mercenary reasons, and I don’t think that ever pays in the long run.

I paint still life when I can’t get out, but my interest is limited. Still, anyone who paints professionally ought to be able to paint a credible impression of almost anything in his or her line of sight.

|

| Beach Grass (Goosefare Brook) by Carol L. Douglas |

Ocean Park is typically crowded in the high season. If we were to be perfectly honest, our paintings would be full of people. I can draw people, so I don’t have much trouble adding them to my landscapes. Still, I don’t often do it. The problem is in meaning.

Yesterday, I set up downtown, looking at a table on a side-porch at

the Curtis. There was nothing especially pictorial about the scene. But it had an evocative quality, suggesting a small, convivial party, relaxing after a day on the beach.

That’s the shell of sociability, and it’s as biographical as the clothes we wear. We recognize it in many places—a lonely writing desk, the objects in the console of another person’s car. In fact, much of still life is intended to suggest character that’s just briefly stepped away. Landscape can do exactly that, too.

|

| Beach Toys, by Carol L. Douglas, 2017. In this painting, the figure is completely neutral, neither supporting nor distracting from the composition. |

And yet the composition was still not satisfying to me. A person reading could add to the sense of stillness and anticipation, I thought. He or she should not be central to the frame, so I set a figure on the rail, feet dangling, a book in her lap. That was a mistake. The dangling legs interrupted the serenity of the scene. I turned the still androgynous figure to the right, in the classical languor of a

Maxfield Parrishnymph. That didn’t work, either, because it’s a silly pose for 2018. However, it gave me the general bounding box of where the figure should fall.

A note: if you’re doing this, have a friend stand in the general area just long enough to make some marks to indicate their approximate height. Even the most perfectly-drawn figure will look ridiculous if it’s too large or small for the scene.

|

| Later, Ed Buonvecchio and I went out to paint in the fog. It seemed like a good place to use my four-way flashers. |

Why did I reject dangling feet and or a figure seated in a chair? Either would have made a good subject for a painting, but they weren’t right for this one. I was feeling the terrific stillness of morning in Maine, and action and presence would have diminished that. In fact, too often, our last-minute tchotchkes end up damaging, not helping, our paintings.

As I was finishing, a lady carefully inspected my painting. It spoke to her on the same level as it spoke to me, so she commissioned me to do another version for her. There’s a lesson there for me: it’s not all composition or technique. People ultimately react to the emotional pull of place. Unless you feel it, they won’t, either.

I’ve got one more workshop available this summer. Join me for Sea and Sky at Schoodic, August 5-10. We’re strictly limited to twelve, but there are still seats open.