Before he became Maine’s greatest painter, he needed to shed his sentimentality. He did that in part by taking up watercolor.

|

|

Five boys at the Shore, Gloucester, 1880, Winslow Homer

|

After working as an illustrator during the Civil War, Winslow Homer concentrated on two distinct oeuvres: postwar healing and homely, nostalgic paintings of American innocence. These were well-received by the public but not universally respected.

“We frankly confess that we detest his subjects… he has chosen the least pictorial range of scenery and civilization; he has resolutely treated them as if they were pictorial… and, to reward his audacity, he has incontestably succeeded,” said writer

Henry James. Winslow Homer’s work in the late 1860s and ‘70s was done in paint, but it was still illustration. When he depicted children as symbols of the nation’s lost innocence, he was playing on a common, well-worn theme of the time.

To be fair, Homer was a young man, and he hadn’t had the advantage of an extensive art education. He was just 29 when the Civil War ended. Snap-the-Whip was finished when he was 36 years old. It was about this time that he was able to give up illustration to focus on painting. It was also around this time that he took up watercolor seriously.

|

|

Three Fisher Girls, Tynemouth, 1881, Winslow Homer, courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

|

By the middle of the 19th century, the influence of critic

John Ruskin led to an interest in watercolor as a serious medium. The American Society of Painters in Watercolor, later to be the

American Watercolor Society, was founded in 1866. In 1873, this group mounted an exhibition of nearly 600 paintings at the

National Academy of Design.

Homer was living in New York at the time and almost certainly saw this show. It’s also probable that he was already familiar with watercolor painting. It was a genteel medium, widely used by ladies and children, but not respectable enough for galleries.

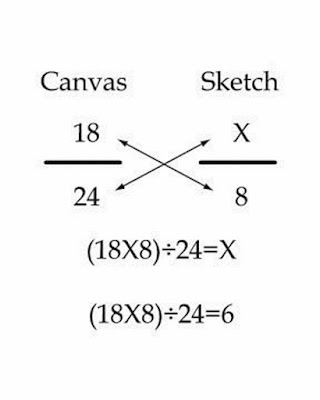

In 1873, Homer left for Gloucester, where he made his first professional watercolors. That summer he sketched and painted children playing on the waterfront. They clam, row, pick berries, play on cliffs and stare longingly out to sea. These paintings were a continuation of his interest in the lost innocence of America.

|

|

The Boatman, 1891, Winslow Homer, courtesy Brooklyn Museum

|

What was different was how he applied the paint. He drew in graphite, and then painted over his drawing. He didn’t wet his paper, which was common practice at the time. This made for a less-detailed, more sparkling finish. Critics were mixed about the results. Some admired the rawness; others hated it. “A child with an ink bottle could not have done worse,”

wrote one.

By the end of that decade, Homer had come to two points in his personal life which would mark his mature work—a tendency to reclusiveness and a fascination with the sea. But before he could become Maine’s quintessential painter, he needed to shed his obsession with the American myth.

|

|

Casting, Number Two, 1894, Winslow Homer, courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

|

He spent 1881 and 1882 in the English coastal village of

Cullercoats, where he focused on the men and women who made their living from the sea. His palette muted; his painting became more universal. And he made much of this transition in watercolor.

He had, by changing up both his medium and his locale, made himself a painter of an elemental truth—the relationship of man and the sea.

Between 1873 and 1905 Homer made nearly seven hundred watercolors, transforming the medium and his artistic achievement as a whole. “You will see,” he said, “in the future I will live by my watercolors.”