A 45-day challenge to make you a better painter.

|

||

|

My workshop monitor, Jennifer Johnson, has spent several winters in Australia. There she bought watercolor paper in an A4 size, which is long and narrow. She’s been bringing it to class. One day she decided to do all three phases as thumbnails on the same page. I immediately saw the value in her idea. I’ve been introducing it to my watercolor students at workshops and classes.My students follow a strict protocol. It starts with a pencil sketch. Oil painters then move that to their canvases as a grisaille; watercolor painters have an intermediate step of a greyscale (monochrome) painting. This helps them make stronger compositions, and allows them to experiment early in the process, when bad choices are easy to reverse.

|

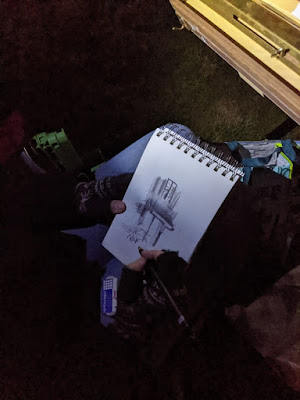

| Jennifer’s field notebook that started this all. |

One of these is Becky Bense, who’s a crackerjack watercolorist. She’s also a friend, so we made a pact at the end of my annual Sea & Sky workshop. We will each do thirty of these three-part compositions over the next 45 days. It wasn’t 30-in-30 because Becky’s more realistic than me. That’s a good thing, because my surgery last week has set me back rather sharply. I’m going to be lucky to finish the thirty by Thanksgiving.

I frequently recommend the book, Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, by David Bayles and Ted Orland. Their takeaway message is that art gets made through consistent everyday practice, not in great fits of genius. Do a little every day, and you’ll get better and better. As a teacher, I see tortoises and hares among my students. The ones who succeed are the persistent ones. Even if you only draw for five minutes a day, you’re advancing your skills.

|

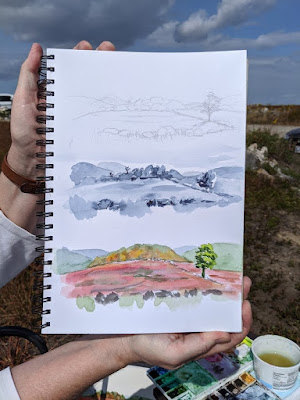

| An example by me. Note that I’m testing the colors on the margins before I lay them down. And I also knocked the garlic bowl over before the last step. Don’t do that. |

Less-experienced painters tend to perseverate, “licking the paint,” as my pal Poppy Balser calls it. That’s because they think their errors can somehow be undone at last minute. They bury their own beautiful brushwork in these last-minute corrections. Working fast, with no great investment in time, prevents that.

Facing a blank slate every day can be daunting. Why not dial it back a little by experimenting with this process? So, without consulting Becky, I’m inviting you to join us. Oil painters can play this game too: all they need is an inexpensive gouache kit. Everything else works the same as for watercolor.

You will grasp the process by looking at the pictures, but I’ll spell it out: do a sketch at the top, a greyscale in the middle, and a small, color painting at the bottom. Ignore the idea of cropping; these are by definition thumbnail sketches. Don’t belabor any of it; half an hour is a good amount of time to do the whole thing.

Sadly, we can’t buy watercolor paper in A4 in the US (at least not easily). You can either buy 12X16 sheets and cut them in half, or buy 9X12. Either is close enough.

|

| It’s all about value. Here are some of my students looking at value at Sea & Sky earlier this month. |

From beginning to end, you’ll be concentrating on value. The sketch is simple, just a drawing with a #2 pencil, but it still should be a value sketch, not just a line drawing. For the monochrome (greyscale) middle picture, mix two complements. I suggest burnt sienna and ultramarine, but you can experiment. Your goal with the final, color, painting is to lay down the paints as immediately, and freshly, as you can. That means hitting the values right on the first try. To do that, mix and check them against your greyscale painting.

I have one more workshop left this season: Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air in Tallahassee, Florida, November 9-13. There are enough students to go, but there are still openings, so I’d be excited if you signed up.

From there on in, it’s all Zoom, Zoom, Zoom until the snow stops flying. My Tuesday morning class is sold out; there are still openings for Monday night Zoom classes.