|

| Rivendell, by JRR Tolkien (Tolkien estate) |

The other day, I found the above picture of Rivendell for a friend, and it struck me anew that J.R.R Tolkien was an accomplished illustrator. He could have worked as an artist had he not had an even greater facility with the written word. “Who taught him to paint?” I mused.

Turns out, it was his mother. After their father’s death in 1896, she moved young Ronald and Hillary to Sarehole, a hamlet that has now been absorbed into greater Birmingham. Mabel Suffield Tolkien was a capable artist and passionately interested in botany. “Ronald can match silk lining or any art shade like a true ‘Parisian Modiste,’” she wrote to her mother-in-law in 1903.

Those lessons ended tragically young, since Mabel died of diabetes when her young sons were 10 and 12. She entrusted his care to Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory. This put him within visiting distance of one of the most important collections of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood painters, that in the Birmingham Museum.

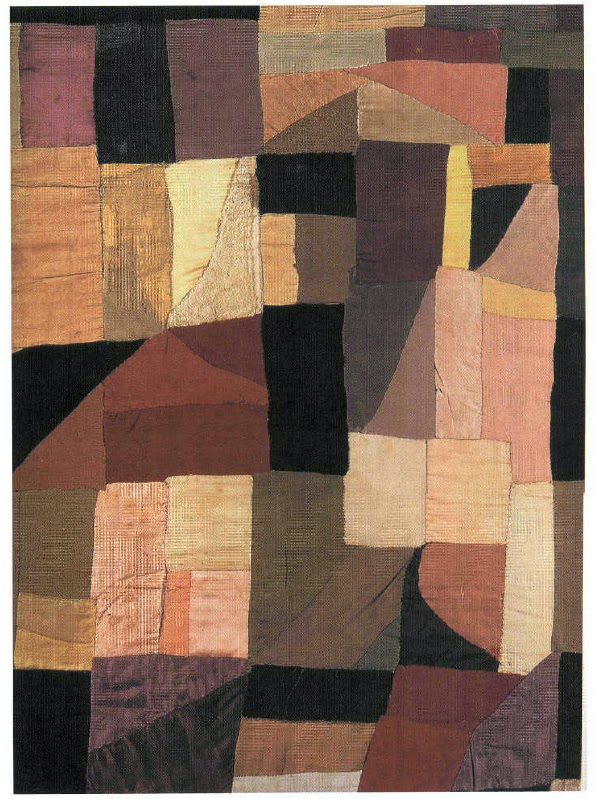

|

| Fangorn Forest by JRR Tolkien was originally done as a Silmarillion painting in the late 1920s, and reflects the current aesthetic. (Tolkien estate) |

That the medieval fantasies of the Pre-Raphaelites would appeal to an adolescent of Tolkien’s temperament seems obvious, but we have a scholar’s word for it. Humphrey Carpenter, author of Tolkien’s authorized biography, wrote that Tolkien associated his childhood gang, the TCBS (Tea Club, Barrovian Society) with the Pre-Raphaelites, indicating that he and his pals were certainly aware of them.

Tolkien began to make visionary pictures after he went up to Oxford in 1911. These included scenes that would later be expressed in words. For his story Roverandom, conceived in 1925, Tolkien made at least five illustrations. In the late 1920s or early 1930s he produced a picture book, Mr. Bliss, in colored pencil and ink. These pictures and others, however, were for his own and his family’s amusement, not for print.

His illustrations for The Hobbit, however, were intended for publication. The first printing of this book, in 1937, contained eleven black-and-white illustrations and maps. Full-color plates were added to later editions.

Tolkien used drawing as a means of understanding the complex topography of his imaginary world. He made many sketches and drawings during the writing of The Lord of the Rings. These have subsequently been published, but his intention was not to illustrate the novel, but to aid in his writing.

|

| Lamb’s Farm, Gedling, (c. 1914) represents a real farm, owned by Tolkien’s aunt. (Tolkien estate) |

“In human art Fantasy is a thing best left to words, to true literature,” wrote Tolkien. “In painting, for instance, the visible presentation of the fantastic image is technically too easy; the hand tends to outrun the mind, even to overthrow it. Silliness or morbidity are frequent results.”

Tolkien continued to paint and draw all his life. His home was supplied with “paper and pencil and a wonderful range of coloured chalks, paintboxes and coloured inks. We knew as we got older that these things gave him particular pleasure, and they continued to do so right through his life,” his daughter Priscilla recollected.

His work was in the style of his times—realism with lashings of the Art Nouveau of his childhood and the Art Deco of his young manhood.

To answer my initial question, Tolkien learned to paint from everybody and nobody. His initial instruction was that of a good, bright, home-schooled lad of his time. He then built on that as an autodidact, absorbing the architecture and art of the world around him. How he applied that to his own inner vision was, of course, his own unique gift.