The same principles apply across all creative ventures. So why don’t women follow the money?

|

| This way blindness lies… |

I’m in the midst of foot surgeries. As you can imagine, I got bored before I got mobile. My daughter is getting married next month, so it was a good time to do handwork for her wedding. I started with fringing shawls for the distaff side of the bridal party. I could do that with my foot elevated.

The artist is intrepid at making stuff. We simply don’t see lack of experience as a problem. We’re often working in areas we’ve never been in before.

| Fringing the shawls was tedious but required little actual skill. |

Sewing, however, is something I can do just fine. If there was money in it, I might have been a couturier rather than a painter. From fringing, I moved on to making the ring-bearer a tartan bow-tie from the scraps of his sister’s shawl. Then, since the mess was all out anyway, I started the flower-girl’s dress. All this has been drawing me upright. I work until my foot throbs and then stop.

|

| The bow-tie took a little more experience. |

Grace’s dress is meant to be a miniature of the bride’s dress. It has a bouffant skirt with horsehair braid on the top layers of tulle. I like this new use for an old material very much, but it’s hard to scale it to a two-year-old.

A two-year-old cannot go strapless, for engineering and other reasons. A train is also out of the question. And somewhere I need to incorporate a big pink bow, which the bride’s dress doesn’t have. As you can imagine, there is only so far a pattern can take you, and we’ve long passed that point.

|

| Barb Whitten’s paper sneakers. A woman who can make those can make anything. |

I copied the first four layers easily enough, but the top layer baffled me. I called artist Barb Whitten for help. She sculpts, so she can think in 3D. She had the layer figured out in minutes. There were eight panels, each with a 90° arc, which meant the skirt encompassed 720° of fabric.

I ran it past another friend, a seamstress and Civil War reenactor. “You realize I had to convert that to 19th century terms, don’t you?” she said. The penny dropped for me. When I saw that wedding gown as a variation on a Victorian gown, the layers made sense.

|

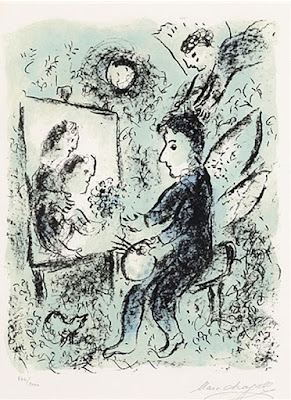

| In the end, it all comes down to craftsmanship. |

But to scale it down and cut the pieces freehand required trigonometry. I don’t care if you call it math or you call it “Granny drawing out a pattern on the table.” It’s the same thing. I guessed it, and then I calculated it, and my numbers were right to a quarter of an inch. So I cut it and sewed it.

Women have been doing this work since the dawn of time. It’s not much different from carpentry. It starts with a vision, which is then sketched, measured and constructed.

That’s also how engineering works. So why are women so skittish about entering engineering as a field? Historically, women have participated in science and engineering at much lower rates than men. That’s sad, because those jobs pay well and are in demand.