Scotland is a stew of genuine Medieval and Victorian architecture, ideas, myths and fables, with a dollop of pop culture thrown in.

|

|

Merlin’s Tomb, 1815, by Joseph Michael Gandy, is a fantasy based on Rosslyn Chapel.

|

The Scotland we imagine was largely the invention of the novelist Sir Walter Scott. It was he who made the legends of the Highlands fit reading for polite society. At the time, Scotland was moving into the modern world of capitalism and engineering. Meanwhile, the Highland Clearanceswere pushing people out of their tribal lands and off to the New World. Scott wrote at this pivotal time in Scottish history, and his stories drew a line between the romantic then and the pragmatic now.

There’s a monument to George IV in Edinburgh; it marks the first visit of a United Kingdom monarch to this city in two centuries. To be fair, much of that time Scotland was in rebellion.

|

|

Portrait of George IV of the United Kingdom, 1829, David Wilkie, courtesy of the Royal Collection. The king actually wore pink tights for his visit.

|

Scott stage-managed the king’s visit. He had just three weeks to plan the event, but succeeded in creating an affair that impressed both the ruler and his own countrymen. Tartan had been banned after the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, but Scott dressed the king up in it. Overnight, tartan became a potent symbol of Scottish national identity.

|

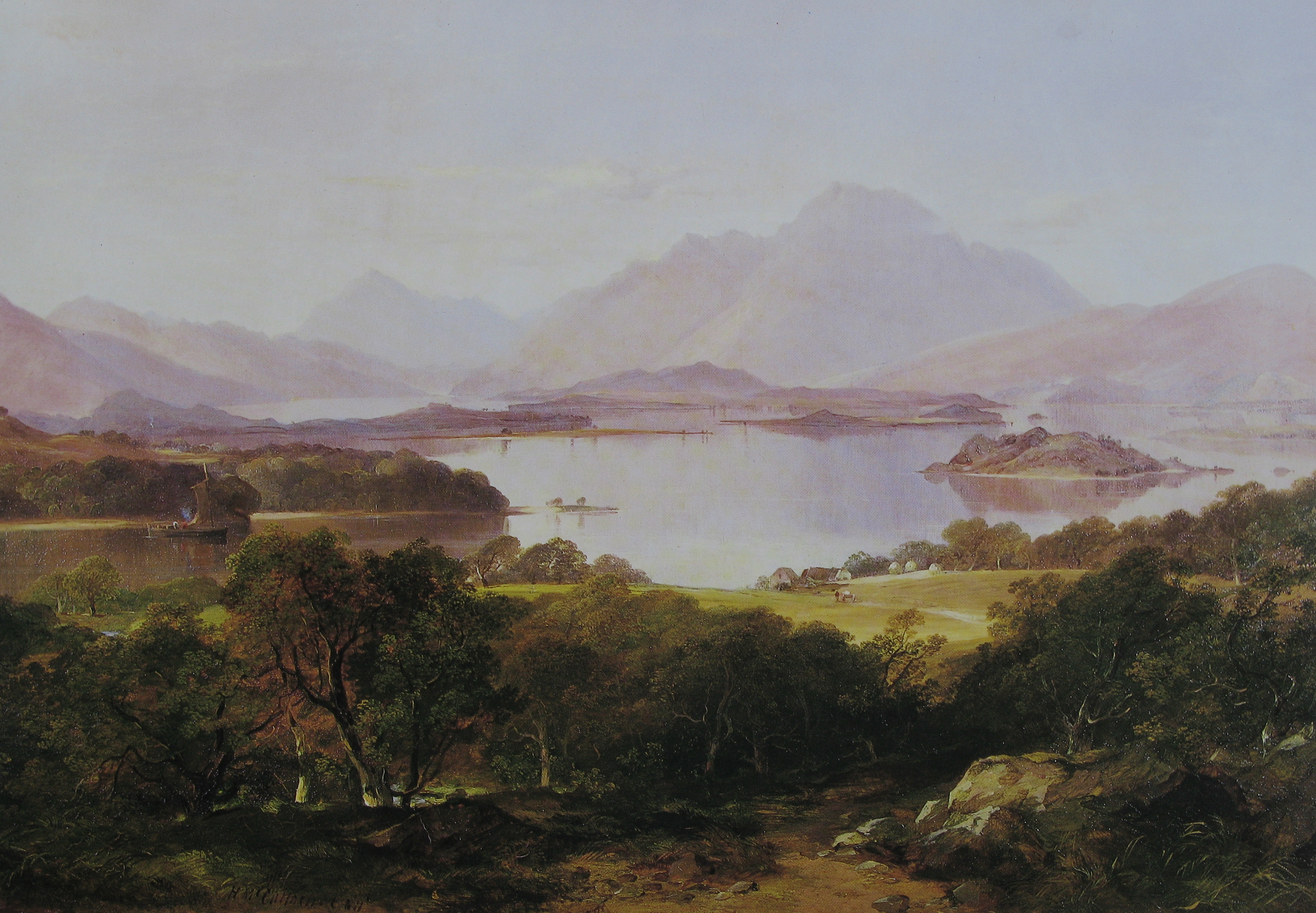

Rosslyn Castle, c. 1820, Joseph Mallord William Turner, courtesy Indianapolis Museum of Art

|

As Scotland went off the boil, many Englishmen visited. Among them was the painter JMW Turner. During his first trip in 1801, he sketched Rosslyn Castle. Later, he returned and painted the Castle for Scott’s serial, The Provincial Antiquities and Picturesque Scenery of Scotland. This teamed the United Kingdom’s greatest romantic writer with its greatest romantic artist. Turner continued to illustrate Scott’s books, becoming enough of chum to visit Scott at his vast country pile, Abbotsford, in 1831.

|

|

Edinburgh from Calton Hill, c. 1819, Joseph Mallord William Turner, courtesy National Galleries Scotland

|

The picturesque was a compromise between two Enlightenment ideals: beauty and sublimity. By the end of the 18th century, thinkers had come to the conclusion that these were not rational, but emotional states. The beautiful was sensual; the sublime provoked awe or terror. The picturesque combined them in a more easily-digested package.

Where better to experience this than in the Scottish Highlands? “The mountains are ecstatic,” wrote Thomas Gray in 1765. “None but those monstrous creatures of God know how to join so much beauty with so much horror.”

Nobody was more susceptible to the Scottish picturesque than Queen Victoria. In 1842, she and Prince Albert paid their first visit to Scotland. They were so struck by the Highlands that they returned regularly, ultimately purchasing the Balmoralestate in 1848.

|

|

View from the walk near the Dee in Balmoral Grounds, 1849, Queen Victoria, courtesy Royal Collection Trust

|

Victoria’s affection for Scotland was deep and abiding. The Royal Couple enthusiastically decorated Balmoral Castle in Balmoral tartan, stags’ heads, and other Scottish tchotchkes. This led to an international craze for all things Scottish.

The queen visited Rosslyn Chapel on her first trip north. It was then half-ruined and overgrown, and she noted that it deserved restoration. Work commenced in 1862, and the chapel was rededicated to worship that same year. Today, Rosslyn Chapel is a stew of Medieval and Victorian architecture, ideas, myths and fables, with a dollop of pop culture thrown in—much, in fact, like the myth of Scotland itself.