Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting is still among the masterpieces of western art that move me most.

|

|

The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow, 1567, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

|

Pieter Bruegel’s birth was unrecorded, but it is thought to have been around 1525-30 in either Liège or Brabant. Just as there is ambiguity about his birthplace, there is no record of whether Bruegel died as a Protestant or Catholic. (He was shrewd; he asked his wife to burn his papers after his death.)

Bruegel’s youthful world was wholly Catholic. His training and early career were excellent and orthodox: apprenticeship to a leading Antwerp painter in the Italianate style (

Pieter Coecke van Aelst), further studies with an artist-priest (

Giulio Clovio) in Rome, a now-lost church altar in 1550-51. The anomaly was Coecke’s wife,

Mayken Verhulst, an artist from Mechelin. This city was an early center for peasant genre painting, and she is sometimes credited with transmitting this idea to Bruegel. (She also trained his young sons after his early death in 1569; art history knows her mainly as the root of the Brueghel painting dynasty.)

Bruegel worked with three themes throughout his career: peasants, landscape and religion. In his early work, these converged and diverged in no particular pattern. As a member of a successful atelier family (he married the Coeckes’ daughter) he flourished; he had a high degree of skill as well. But his most brilliant paintings were at the end of his life. Was that simply because he had grown to maturity, or was he responding to the trials of his times?

|

|

The Census at Bethlehem, 1566, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

|

One of the decrees of the Council of Trent was that religious painting must be suitably elevated; saints must be set apart from mere mortals in dress, demeanor and activity. The Church recognized that saints with dirty feet were a dangerous endorsement of the Protestant concept of a priesthood of all believers.

By then, Reformation was smoldering in the Netherlands; Anabaptists and Calvinists met secretly and illegally. Bruegel left no record of what he thought of this or anything else. But from a Catholic standpoint, his paintings became positively impertinent. Of these paintings, three deserve mention. Bruegel located his Tower of Babel (1563) in a Flemish city and dressed Nimrod as a European king. The Sermon of St. John the Baptist (1566) is militant—subversive, actually—because it clearly depicts a contemporary Calvinist or Anabaptist service. In it he identifies the heretic Protestant preachers with John the Baptist. The Adoration of the Magi of 1564 is a straight-up Nativity scene, but anything but saintly. Notice Mary’s droopy veil, Joseph’s distraction, and the brutish faces of the peasants to his right.

One could ask whether these reflected the views of his patrons or his own religious convictions. I would guess that the two were so intertwined that the question is meaningless.

|

|

The Tower of Babel, 1563, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

|

How powerful art can be! In 1566, the Reformation ignited in the Low Countries. It did so over the issue of art, in the form of the

Beeldenstorm (“picture storm”), in which church art was systematically destroyed throughout the Netherlands. Spain responded by sending the cruel Duke of Alba to Brussels (where Bruegel had settled) to extirpate the rebels. This reign of terror—in which thousands died and many more were dislocated—led directly to the Eighty Years’ War.

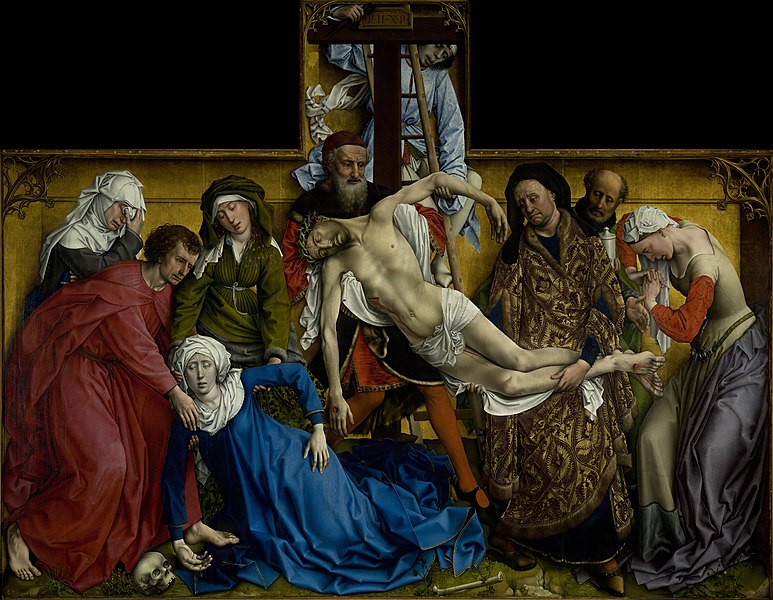

It was during the height of this terror that Bruegel painted The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow. It’s lovely, but it isn’t peaceful. The central stream of figures is very nearly on the march.

This weekend I uncrated a set of porcelain crèche figures. They are clichéd and indistinguishable from millions of others worldwide. Our museums are full of similar Nativities—some brilliant, many not. Some religious art slipped over the line to idolatry, and much was commissioned for base reasons of power and prestige. The

Beeldenstorm set out to destroy the fruits of these bad intentions, but it destroyed indiscriminately. In his last years, Bruegel was feeling his way along the narrow space between the

Beeldenstorm and the Duke of Alba. Today we see his

Adoration as quaint; we don’t remember that it was radical.

The Protestant impulse forced a new way of painting. Artists couldn’t produce idols, so the pattern books of their faith—unchanged for a millennium—were closed to them. How, then, could they articulate their religious feelings? Bruegel actually painted three winter scenes of the Biblical Infancy Narratives. The others are The Slaughter of the Innocents (1565-66) and The Census at Bethlehem (1566).

Bruegel was addressing a problem which bedevils our own age: how can the artist tell an ancient, unchanging story in a new language? He solved the problem by quoting a traditional icon in the context of a new reality. In these three paintings, the new context was the Protestant priesthood of all believers, represented by the peasantry. Today we call this “appropriation art” and imagine it’s a new idea.

|

|

The Slaughter of the Innocents, c. 1565-67, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

|

The Nativity (particularly the Virgin and Child) is the most commonly painted subject in art. Even in our secular age, even among non-Christians, it is universal. Bruegel’s brilliance was in realizing that he didn’t need to spell out the scene inside the stable; everyone knew it. In fact, in not doing so, he allowed us to regain something mysterious and personal about that night.

I must mention Bruegel’s technical prowess. Since he invented the winter landscape, he can also be credited with chromatic modeling in snow, in the form of violet shadows and the warm highlights. Note how the roof in the building on the top left is shaped by these shifts in color rather than with darker grey shadows. (This was an artistic choice; the snow on a dark winter day is generally flat.) The dark mass of people sweeps in an arc to the Nativity, pulling it back up into importance. Bruegel emphasized this sweep by making it the busiest part of his painting, and by making the figures darker and in greater contrast than the surround. This arc of humanity plays off against the perfectly composed diagonal lines of the surround.

Bruegel was an acute observer of reality. I respond to his winter scenes because they are true to my own experience, even if the details have changed beyond all imagining. I respond to his religious vision because I spent decades feeling my way gingerly between Protestantism and Anglo-Catholicism.

(This was originally published on December 11, 2007.)