If you don’t rejoice in the good times, you’ll have no resilience when the bad times come.

|

| Breaking Storm, by Carol L. Douglas. I missed painting American Eagle’s fitout this year because I’m quarantined. |

People ask me how I know when a painting is done. “When I’m sick of working on it,” I answer. All creative work is a compromise between our vision and capabilities. This means not just skill but environmental factors. If you doubt that, try singing through a headache.

Our current crisis involves more compromise than usual. Our supply chain is broken in odd ways; that includes some scarcity of art supplies. Carol at Salt Bay Art Supply in Damariscotta told me she runs low on white and black paint first. The white I understand; black, however, is a mystery to me.

Hammond Lumber has been great about accommodating my quarantine, but they can’t send me what they don’t have. That includes color charts. Each time I climb on a ladder to work on my current project, I wince at the state of the crown moulding. It needs paint, but I can’t match the other white in the room without a color chart. It’s difficult, but I’m deferring the trim to some future time.

|

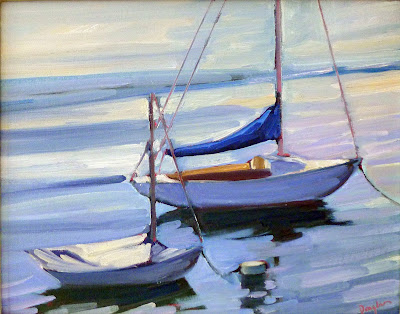

| Cadet, by Carol L. Douglas |

I commiserated with two well-known artist friends yesterday. “This has me working twice as hard to look for ways to continue to make a living,” said one. The other has taken a night job to feed his family. “I can still paint during the day,” he said. They both have school-age kids and are making compromises to survive.

We live in a pandemic mindset. In some ways, that’s liberating. There has been blessed silence about some of our previously-consuming passions. Food allergies, the upcoming elections and gender identity are three things I’m happily not hearing about right now.

The bleak, short days of winter seems halcyon in retrospect, even if I didn’t have the Christmas I thought I wanted. It’s a pity that we so often ruin the present with our anxieties. Seizing the day is not just a recipe for overall happiness; it gives us the strength to roll through the bad times when they (inevitably) come.

|

| Flood tide, by Carol L. Douglas |

When a mother takes a newborn home from the hospital, she is overwhelmed with physical and mental fatigue. Years later, that isn’t what we remember first; we remember our joy. I’m not sure why the human mind is wired this way, but it’s something we have to work to overcome.

The Black Death was the most devastating pandemic in human history. It killed a third of Europe’s population and around 20% of people worldwide. If you lived through it, it was an unmitigated horror. Yet it ultimately broke the caste economy of the Middle Ages. Serfs could leave the manor and find work, which freed most people from a life no better than slavery. Land prices dropped. Meat consumption rose, because you can raise cattle with fewer hands than you can raise corn. In fact, the plague set the conditions that eventually led to the creation of the middle class.

All of which is to say that not every disaster is an unmitigated disaster. Sometimes, trouble is a way for society to kick off its stays and try something new. What if these turn out to be our Good Old Days?