Natalie MacMaster is touring with her husband, Donnell Leahy, playing in the hotspots of Caribou, Rockland and Brownfield, ME before heading off to the bright lights of New York and Boston. We jumped at the opportunity to see them in the intimate Strand Theatre in Rockland last night.

MacMaster is a member of a famous Cape Breton fiddling family that included the renowned fiddler, Buddy MacMaster, among others. Cape Breton fiddling is the older brother of Highland fiddling, transported to Nova Scotia after the Highland Clearances. Once you’ve heard it, it needs no further introduction.

Leahy, who’s Irish, toured extensively with his seven siblings. His style of playing is more emotive, throatier. “I grew up in Ontario without that kind of [Cape Breton] style around me. But I listened to my father play the fiddle. I listened to the radio. I listened to accordion music because I had a friend who was an Irish accordion player,” he said.

As you can imagine, they’re both superlative players. But they were not the stars on the Strand stage. That honor went to their five eldest children: Mary Frances, Michael, Clare, Julia, and Alec. (Baby Sadie sat out the show.) The kids played the fiddle. They step-danced. They sang The Mary Ellen Carter. Their teenaged cousin has extended his winter break from school and is traveling with them, playing the pipes.

|

|

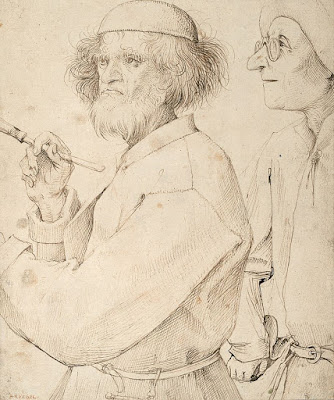

The Painter and the Buyer, 1565, was a self-portrait by proud paterfamilias Pieter Bruegel the Elder

|

With such a family legacy, it’s no surprise that the kids are about ready for their first big break. That’s coming soon, with an appearance scheduled on Steve Harvey’s Little Big Shots later this year.

Artistic dynasties like the Leahy-MacMaster clan are now rare, but that hasn’t always been so. There was the Boothfamily, who are now remembered mostly for their ignominious assassin. The family of Johann Sebastian Bach included 50 musicians of note for two centuries. The same is true for the descendants of the Dutch painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. For women like Artemisia Gentileschi, a family workshop was a safe space to pursue an unconventional career. And there is, of course, Maine’s own Wyethfamily. I could go on for pages.

|

|

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, 1638–9, is by Artemisia Gentileschi, who had the advantage of being trained in her father’s workshop.

|

What has changed? Public education tends to dilute parental influence even as it democratizes knowledge. Children are in school while their parents are in offices far away. Fewer children are being trained in any craft now, as we educate a nation of generalists. Moreover, we expect our children to self-actualize, to make and follow their own dreams rather than go into the family business.

Watching the Leahy kids on stage with their parents, I’m inclined to think we need more of that, and less factory education. I look forward to their future careers.