If you’re trying painting for the first time, it makes sense to use less-expensive equipment and supplies. Here are corners you can cut.

|

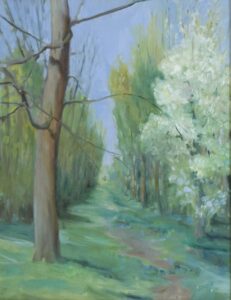

| Early Spring on Beech Hill, 12X16, oil on canvas, $1449 framed includes shipping to continental US. |

In 2018, when I first wrote about plein air painting on the cheap, this pine tripod easel cost $7.99. It’s ‘on sale’ for $14.99 now, a whopping 53% price increase in four years. That’s precisely why, if you’re interested in trying plein air painting for the first time, you should probably think about ways to do so on the cheap.

That’s the same easel I learned on in high school. I still have it today, tucked into the corner of my studio. It’s rickety, awkward—and it works. It was a standard style field easel until the invention of pochade boxes that screw onto tripods. My father painted his whole life with a similar, home-made model.

|

| Bridle path, 11X14, $1087 framed includes shipping to continental US. |

This easel, however, requires some sort of table. My thrifty friend Catherine uses an old TV table, but there are lighter versions now available.

I wrote recently about pochade boxes for every budget. Dollar Tree’s 9X13 baking pan has only gone up to $1.25, so you can still make the cheapest possible palette for $2.50, plus duct tape. What I neglected to mention in that post was the possibility of buying a used pochade box. Some of my best art tools were purchased second-hand. But you must have the time to be patient.

If you’re handy, you can make one like I did. Or, there’s the classic cigar-box pochade.

|

| Best Buds, 11X14, $1087 framed, includes shipping to continental US. |

One of the great advantages of watercolor is that it doesn’t require any easel. Many studio oil painters sketch in watercolor in the field. A Winsor & Newton Cotman field set and a watercolor journal are a cheap, lightweight introduction to wilderness painting. That’s essentially what Thomas Moran carried on the Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871. He’s known as an oil painter, but his watercolors have an important place in art history.

In every media, the difference between professional and student grade paints and pastels is the amount of pigment and the quality of the binders. In some cases, more expensive pigments will be copied with hues. A hue mimics the color of a single-pigment paint with less-expensive materials. For example, “cerulean blue hue” is often a combination of zinc white and phthalo blue.

A better solution is to avoid pricier pigments in the first place. In earth colors, there’s almost no difference between the student brand and the professional brand. The difference shows up in paints like the cadmiums, where the pigment itself is expensive. There are modern substitutes that do the job equally well at a lower cost.

|

| Blueberry Barrens, 24X36, $3985 includes shipping in continental US. |

There are decent student-grade brands out there in all media:

Oils: Gamblin 1980 and Winsor & Newton Winton.

Acrylics: Winsor & Newton Galeria and Liquitex.

Watercolors: Winsor & Newton Cotman or Grumbacher Academy.

Pastel: Alphacolor Soft Pastels

If you decide you love plein air painting, you can replace these student-grade colors with professional-grade paints over time.

Brushes don’t have to break the bank either. Even though I have a slew of fine watercolor brushes, I still reach for my Princeton Neptunes. Oil and acrylic are trickier since cheap brushes sometimes drop bristles in your work. Princeton also makes good, inexpensive oil/acrylic brushes, especially their 5200 and 5400 series. If you want a synthetic brush, make sure it imitates hog bristles, not sable. A softer brush isn’t meant for alla prima painting.

It’s plein air season again. Check out my workshops, here.