Canaletto did not use a camera obscura. People repeat that because they’re uncomfortable with the fact that they can’t draw.

|

|

Westminster Abbey with a procession of Knights of the Bath, 1749, Canaletto.

|

It has long been held that Canaletto achieved the amazing accuracy in his vedute through the use of the camera obscura. This is not a modern thesis, although it is widely repeated as fact. It came down to us from Canaletto’s earliest biography, written in 1771, but it’s convenient for our modern sensibilities. After all, Canaletto’s landscapes are so perfect, they could not have been rendered from life—could they?

The Royal Collection Trust has released a report that seems to prove, conclusively, that this theory is wrong. While infrared technology is often used to examine what’s under the surface in oil paintings, it’s not commonly used on drawings. The Trust applied this technique to their collection of Canaletto’s works on paper. This is significant; they own a third of known Canaletto drawings.

They discovered the ruler edges, pencil markings and other traces of the drawing process under the finished surfaces. It was enough for the curators to state “categorically” that the stories of Canaletto’s use of the camera obscura were mythical.

|

|

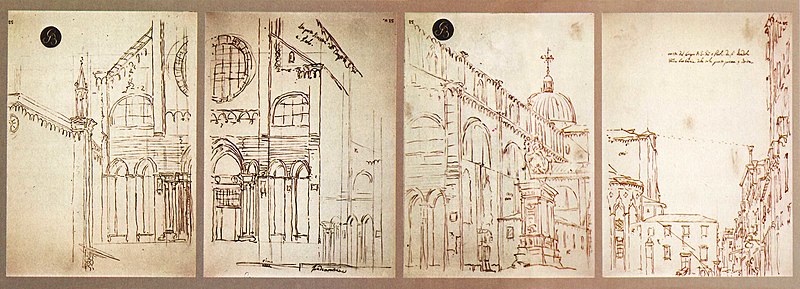

Architectural Capriccio, drawing, Canaletto. “Capriccio” means it’s a fantasy landscape.

|

There is nothing inherently wrong with the camera obscura or any other mechanical aid to drawing. Nor was David Hockney revolutionizing the art world when he proposed that our ancestors used it. Leonardo da Vincidescribed its workings in 1502, and a similar pinhole drawing device was illustrated in Albrecht Dürer’s Four Books on Measurement. For Canaletto, born simultaneously with the Age of Reason, the temptation to try the camera obscura would have been overwhelming. But he would have quit for the same reason many mature artists stop working directly from photos:

The results are boring.

|

|

The Stonemason’s Yard, 1726–29, is considered Canaletto’s early masterpiece.

|

What is seen by the human eye, with its pronounced center pole, is so much more interesting than the flattened line of ‘real’ optics. That is why our photographs so often disappoint us, and why photography really is a lot more complicated that simply pointing a camera and firing away.

The popularity of the Hockney thesis lies in an uncomfortable fact: by and large, moderns don’t draw well. We haven’t put in the hours with ruler, pencil and paper. We rely on viewfinders, photographs, and other devices for our underpaintings. Rather than face up to that deficiency, it’s easier to imagine that drawing is impossible.

Of course, it’s not, and nobody can really paint until they master the elements of drawing. Too often, modern landscape painting is about fragment and impression. Is that because fragments are so interesting, or because we’ve given up on drawing?