In the solitary splendor of Canada, these painters found energy, possibility, and a national identity.

|

|

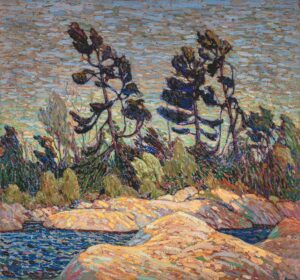

Byng Inlet, Georgian Bay, 1914–1915, Tom Thomson, courtesy McMichael Collection |

Here in Maine, we import our weather from Canada. In fact, we share a lot with our Canadian neighbors, including black spruces, granite, and the spodosol soils that are good for growing potatoes, blueberries, evergreens, and not much else.

Maine has a contemporary painting style that’s driven by this sense of place. It’s curiously unrelated to our most famous summer painter, Andrew Wyeth. Instead, it derives from an earlier generation of painters, including Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper. Maine is just too sunny and wild to sustain Wyeth’s quiet melancholy.

|

|

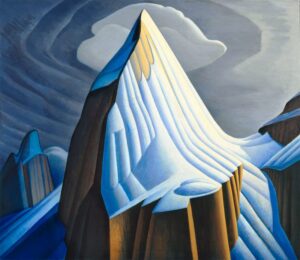

Mt. Lefroy, 1930, Lawren S. Harris, courtesy McMichael Collection |

This combination of influences and landscape gives us some curious parallels to our Canadian neighbors, the Group of Sevenpainters. This group consisted of Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, AY Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, JEH MacDonald, and Frederick Varley. Later, AJ Casson, Edwin Holgate and LeMoine FitzGerald joined them.

|

|

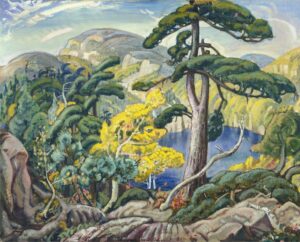

Bright Land, 1938, Arthur Lismer, courtesy McMichael Collection |

Although he died before the official formation of the group, Tom Thomson was a profound influence on them. Emily Carrwas never an official member as she lived in Vancouver, but she was influenced by them. Lawren Harris, in particular, was a support. “You are one of us,” he told her.

|

|

Shoreline, 1936, Emily Carr, courtesy McMichael Collection |

Harris was one of the driving forces behind the Group of Seven, and the most able to articulate their mission. He was a very malleable painter. He went from impressionism to art nouveau realism to complete abstraction in a matter of two decades. His break with realism occurred in the early 1930s, after he visited and painted in the Arctic.

Harris believed in the arctic as a living force: “We are on the fringe of the great North and its living whiteness, its loneliness and replenishment, its resignations and release, tis call and answer, its cleansing rhythms. It seems that the top of the continent is a source of spiritual flow that will ever shed clarity into the growing race of America.”

|

|

First Snow, Algoma, 1919/1920, AY Jackson, courtesy McMichael Collection |

The Group of Seven painted this ethos. In the solitary splendor of Canada, they found energy, possibility, and a national identity. That’s an idea that has become politicized in recent years. Indigenous people have argued that these areas were always inhabited. The depiction of emptiness was a de facto endorsement of the pernicious policy of terra nullius.

But for artists trained in Europe, many of whom saw duty in WWI, Canada was desolate. As AY Jackson wrote, “After painting in Europe where everything was mellowed by time and human associations, I found it a problem to paint a country in outward appearance pretty much as it had been when Champlain passed through its thousands of rock islands three hundred years before.”

|

|

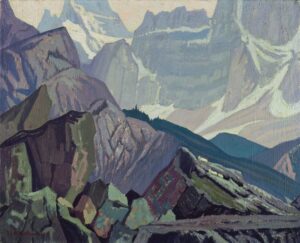

Goat Range, Rocky Mountains, 1932, JEH MacDonald, courtesy McMichael Collection |

I’ve painted through every Canadian province and Yukon Territory. (Nunavut and Northwest Territories remain on my bucket list.) To my American eyes, Canada is empty, and that’s its attraction. Canada is unique in having so much wilderness, untouched, in the modern world. That Great White North, which reaches down and embraces the country in an iron grip every winter, is wilderness’ fierce protector.

Everything the Group of Seven painted derives from that unique understanding of wilderness and its value. Maine artists work from the same wellspring of inspiration, so it’s no wonder that our paintings look similar to our Canadian neighbors’.