What will happen to our work when we die? Most of it will be destroyed, of course.

With its imposing Romanesque spire, the former St. Francis Xavier Church looms over its surrounding neighborhood. This is working-class Black Rock, at the northernmost tip of the city of Buffalo, but the church isn’t unique. As was true in so many northeastern cities, the Catholic Church was the center of working-class and immigrant life in Buffalo. Stand on the top of the parking ramp on the Broadway Market and try to count the spires surrounding you in the East Side. You’ll lose track before you finish.

Having grown up in a Catholic family in Buffalo, I’ve been in many of these churches. Their parishes may have slumped into disrepute, their worshippers moved to the suburbs, but as long as there were people around to care for them, their sanctuaries were treasured spaces.

What the mega-church is to modern worshippers, the 19th- and early 20th-century Catholic church was to immigrants. Some of them, like

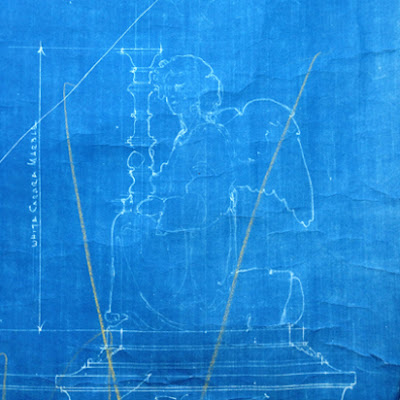

St. Stanilaus, Mother Church of Buffalo’s Polish community, seated thousands in their heyday. They were filled with beautiful windows, statuary, paintings and tile work, often imported at great cost from Europe.

A combination of demographics and scandal has led to many of those great churches being shuttered. What to do with them is a problem facing cities like Buffalo. They’re not suitable for most modern purposes (including worship), but they are too important to tear down.

St. Francis Xavier Church has moved on to new life as

the Buffalo Religious Arts Center, founded in 2008. Its vision is acute and forward-thinking, so much so that I’m afraid it’s ahead of its time. Usually a period of iconoclasm and destruction must be endured before we sweep up the few remaining bits of art and hang them on museum walls.

This came to mind because I was recently asked a related question: “Have you made any provision for what will happen to your unsold artwork when you die?” It was such a cheerful thought that I took the

living willI’d been filling out and stuffed it in the woodstove.

Like every artist, I have a pile of unsold artwork hanging around my studio. What happens to it will be determined by the market, not me. If my work is selling well at the time of my death, my kids can hire an art curator to market it posthumously. If I’ve been forgotten in the scrap heap of time, they can take my unsold paintings out to the burn pile and get rid of them. Once I’m dead, it’s of no importance to me.

That’s the first step in the inevitable winnowing of an artist’s oeuvre, and in fact, until recent times, nobody really thought much about it. It’s what drives up prices for dead artists’ work.

Looking at what we have in museums is, in fact, very instructive about this process. It’s absurd to think that no artists before the Impressionists ever sketched a meadow or drew an abstract sketch, but very few examples of these survive. The Greeks and Romans left us the pantheon of gods and heroes. Medieval and Renaissance art was concerned with our relationship with God. Landscape sketches and abstractions weren’t important to the culture of the time, so they were ignored and ultimately destroyed.