A great artist passed away last month, but I doubt you’ll read about him in art history class.

|

|

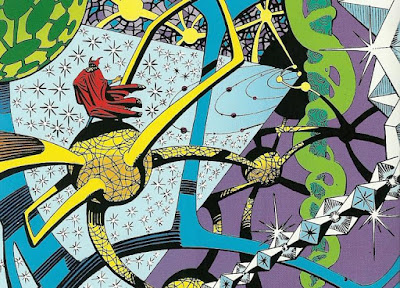

From The Avenging World, 1973, Steve Ditko, published by Bruce Hershenson.

|

I was introduced to the Silver Age of Comic Books by my husband when we were just teenagers. He still sends me great frames by Steve Ditko and Jack Kirbyto study. I believe I’d have been a better artist if I’d studied cartooning first, because these two artists manage to pack a world of action and insight into a canvas only a few inches across.

Steve Ditko passed away at the end of last month. True to his reclusive nature, he died so quietly that nobody is sure of the date.

Ditko was a Slovak from Pennsylvania steel country. He grew up reading Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and Batman, idolizing the latter’s Jerry Robinson. On graduating from high school, he immediately enlisted in the US Army and served in occupied Germany.

|

|

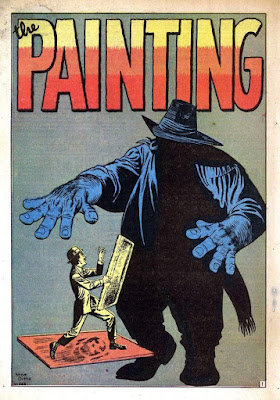

From The Amazing Spider-Man #31–33, 1965, by Steve Ditko and Stan Lee, Marvel Comics.

|

After demob, Ditko enrolled in the Cartoonist and Illustrators School in New York. This had been founded three years earlier with just three teachers—one of whom was Robinson—and 35 students. Most of them, like Ditko, were there on the GI Bill. The school would grow up to become the School of Visual Arts.

Ditko began drawing professionally in 1953, working for a brief time with Jack Kirby. From there he moved to a low-budget publisher called Charlton Comics, producing science fiction, horror, and mystery stories. In 1954, he contracted tuberculosis and returned to his parents’ home in Johnstown, PA to recuperate.

|

| From Dr. Strange, by Steve Ditko, published by Marvel Comics. |

When he got back to New York in 1955, he began drawing for Atlas Comics, which would later morph to Marvel Comics. His contributions to Strange Tales again paired him with Jack Kirby. These books were not comic at all, but the predecessors of graphic novels and intended for adult readers. They were odd, provocative, dystopian and literary, and they included masterpieces of visual art.

Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee originally tapped Kirby, his chief artist, to draw his new superhero, Spider-Man. Lee hated Kirby’s approach. “Not that he did it badly,” said Lee. “It just wasn’t the character I wanted; it was too heroic.” Ditko got the job. Spider-Man debuted in August, 1962 and was quickly given its own series. Ditko was eventually also given writing credit.

|

| Ditko caught the arc of American anxiety. |

Ditko created the character of Doctor Strange in 1963. The art was weirdly prescient as America moved into the psychedelic era. It suggested a different time-space dimension, bizarrely spacious, often anxious. It grew increasingly more complex and abstract as the comic matured.

Ditko and Lee stopped speaking, and eventually Ditko moved on. The real reason for the rupture isn’t known, but it was almost certainly based in clashing artistic visions.

From there, Ditko drifted. “By the ’70s he was regarded as a slightly old-fashioned odd-ball; by the ’80s he was a commercial has-been, picking up wretched work-for-hire gigs,” wrote Douglas Wolk in 2008. Ditko retired from mainstream work altogether in 1998.

|

| And my all-time favorite, from Journey into Mystery Vol 1., courtesy of Marvel Comics.

|

Ditko never married or had children. He didn’t have particularly close relationships with friends. All he ever cared about was his work. Even when he was done with major publishers, he continued to draw for eight hours every day, self-publishing his own Objectivist screeds. “I do those because that’s all they’ll let me do,” he grumpedat the New York Post.

It wasn’t Ditko who had changed; it was the world. The Silver Age of Comic Books was over, and there was nothing fashionable in Ditko’s worldview.