In the midst of crisis, new traditions are created.

|

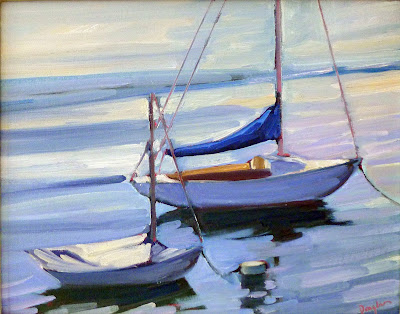

| Soft September Morning, oil on canvas, by Carol L. Douglas, was a painting commission. |

This week, I drove south to deliver a painting. The client is a redoubtable Yankee lady: straight, strong and smart. Her home is a classic Yankee house. It started as a tiny Victorian cottage and grew pell-mell over the generations.

We got talking—as women do—about the holidays. She had ordered a 28-pound turkey for Thanksgiving. Her family is close, and she normally sets a magnificent table using her grandmother’s linens and her best flatware and dishes.

|

| Fallow field, oil on canvas, by Carol L. Douglas, is available for investment. |

Then COVID got worse and our restrictions grew tighter. A 28-pound turkey between two older people is as close to eternity as one wants to get, and she barely outweighs that bird. However, she was obliged. So, she cooked her traditional Thanksgiving feast anyway, and carefully boxed it up. “I had a chart telling me which package went with what so that everyone had enough for dinner and for leftovers,” she said. At the appointed time, her family drove in and collected their Thanksgiving dinners. “The kids were so happy to see their cousins,” she said, “even out in the driveway.”

And—bam—in the midst of crisis, a new tradition is created. “Remember the year we had Drive-Thru Thanksgiving?” those kids will recall as they themselves morph into redoubtable old Yankees. And they’ll remember their resourceful, optimistic, loving grandmother.

|

|

Tête-à-tête, by Carol L. Douglas, was a commissioned painting. |

From there I went to another client. She had to move in a hurry and bought her new house in a sellers’ market. There were a lot of expensive repairs. The painting I delivered is of her old home, and it will have pride of place because she misses it. But she believes God has placed her there ‘for a reason and a season,’ as we evangelicals are wont to say. She sent me along with a jar of homemade applesauce.

My little dog occasionally needs a stop, so we found a dog park along the way. There was one other human there. She told me she’s planning on buying a van and hitting the road when her only child starts college next fall.

“I haven’t been anywhere for 18 years,” she said. She must have been a very young mother, because she barely looked much over 18 herself. I suggested her son might want a room to come home to, but she’d already thought of that. “His grandparents live here, and they have a room for him, and for me,” she said.

| Midsummer, oil on canvas, by Carol L. Douglas, is available, and it’s a statement piece; it’s large. |

Why not? If not now, when? I’ve traveled and camped alone and I recommend it. The bears are unlikely to bother you and the human predators prefer easier pickings. The message she’ll send her son is powerful—you can chart your own course in this world.

I don’t often talk about paintings as investments, but this year has got me thinking about diversification. Like many Americans, my husband and I don’t have pensions. Our retirement savings are invested in mutual funds. The stock market has had a great run, but now I’m thinking about diversifying my own portfolio.

Art is a very illiquid asset. You’re not going to sell it quickly to make a buck, and you should only invest in it if you know something about art to start with. Having said that, the global art boom is here to stay. Worldwide art sales surpassed $67 billion last year. That’s an objective measure of value.

The great beauty of art is that you get to enjoy it while it appreciates (which is not true of my IRA). That means you don’t have to feel self-indulgent if you buy a painting; it may be the best thing you ever did for your heirs.