No wonder people don’t take art seriously as a profession.

|

| Vilanova’s raincoat, hanging next to an exhibit about Picasso. Hanging it next to a large monochrome picture was great design… by the curator. |

A few days later, she returned to Musée Picasso, only to be immediately arrested.

The artist, Oriol Vilanova, expressed mild surprise that the museum’s security was that lax. They countered that they’d already spoken to him about the risks of hanging a jacket on a nail, and he’d refused to tighten it down. The idea, he pointed out, was that visitors should be free to rifle through the pockets and leaf through the postcards within.

The perp has widely been described as ‘elderly’. That is too often a synonym for ‘clueless’ in these stories. In fact, I suspect she was on Vilanova’s secret payroll, since she catapulted his work into a one-day wonder.

The piece has traveled to other venues since 2017. If the coat is hung next to a Picasso, for example, the pockets are stuffed with postcards of other Picasso paintings. On its own, it’s a fairly thin idea.

La Parisien, which originally reported it, said that this woman had converted the work to a mise en abyme.

A mise en abyme is an image within an image, often repeating indefinitely. With the advent of computer science, we’ve started to call that recursion, as it resembles something that happens in software and mathematics.

|

|

Las Meninas, 1656-57, Diego Velázquez, courtesy of the Prado |

But a mise en abyme doesn’t have to be a straight-up copy; it can be a reference, as in Diego Velázquez’ Las Meninas, where the artist frames his subjects in the context of having a portrait painted.

This 17th century painting looks for all the world like a snapshot. It’s a portrait of the five-year-old old Infanta Margaret Theresa, who is, in turn, surrounded by her personal coterie of attendants, dogs and dwarves. Velázquez himself is in the picture, as are the hazy images of the king and queen in the mirror in the background.

It is daring, inventive, complex, weird and mysterious. It’s fascinated viewers for almost four hundred years. In comparison, I wouldn’t be fascinated by Vilanova’s recursion for fifteen minutes.

|

|

Raincoat hanging over forsythia, 2022, Bruce McMillan, courtesy of the artist. I like it better than the original piece, since it subtly references the issue of our day, the war in Ukraine. |

Bruce McMillan, who first pointed out this story to me, asked:

Art installation

on a rainy day

of an artist’s raincoat

hanging over the

flowers the artist

paints where art was to be,

or with unseen eyes

not to be, that was

the silent art question.

I’m afraid I have to come down firmly on the ‘blind’ side. The question Vilanova raises about art reproduction is sophomoric.

|

|

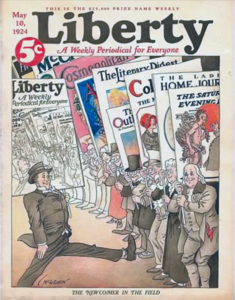

A mise en abyme from 20th century commercial art. |

There is much in contemporary art that I like, but equally much that I resent. We’re enduring a time of relentless tearing down of western values. That includes the values we have traditionally revered in art: intellect, craftsmanship, beauty.

Western civilization has made us the fattest, happiest, most-literate society in the history of mankind. Even our poorest citizens are wealthier than most of the world. We haven’t endured warfare in our own country since 1865. Our kids have never known true economic privation.

These times are, historically speaking, an anomoly. They’re also an incredible blessing, but as Joni Mitchell once sang, “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone.”

Bananas taped to walls? Raincoats stuffed with postcards? They make a mockery of the importance of art, with little serious thought behind them. A little Dada goes a long way, and we’ve endured a century of it so far. No wonder people don’t take art seriously as a profession.

,_by_Velazquez.jpg/521px-Las_Meninas_(1656),_by_Velazquez.jpg)