Drawing drapery isn’t a dated skill; it’s as fundamental to the t-shirts and skinny jeans we wear today as it was to the gowns, kirtles, jerkins, doublets and linen chemises of the 16th century.

|

|

Drapery study, Albrecht Dürer, undated. |

I spent a lot of time painting the human figure at the Art Students League, but I never studied drapery, unless you count the drapes that might be behind a model or still-life. That’s typical, but unhelpful. In the real world, artists are far more likely to draw the clothed figure than the nude.

“The masters must be copied over and over again,” wrote Edgar Degas, “and it is only after proving yourself a good copyist that you should reasonably be permitted to draw a radish from nature.” In that spirit, I’ve illustrated this post with a series of drapery studies by the Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer. I suggest you copy them not on paper, but in creating a drape—and then draw from your draped copy.

|

|

Drapery study, Albrecht Dürer, 1506. |

The t-shirts and skinny jeans we wear today are worlds apart from the gowns, kirtles, jerkins, doublets and linen chemises of the 16th century. Modern clothing is more formless and forgiving than ever. But the principles, regardless of the fabric, remain the same.

Wherever fabric is held down or comes into contact with the underlying support, it creates a pivot point. That point is a hub from which folds radiate. That’s easiest to see if you hold a towel in your hand and let it drape. Where you’ve pinched it is the hub from which all folds originate. If you hold the same towel in both hands and let it drape, you’ll see the collision of folds from two pivot points.

|

|

Drapery study, Albrecht Dürer, undated. |

In clothing, there are often several points of contact, creating several different hubs. Across the back of a shirt, our two shoulder blades strain the cloth in opposition to each other. In jeans, our knees, ankles, derrieres and hipbones are all in contact with the fabric. Even in tight jeans, there will be folds, albeit subtle. Wherever the figure presses against the fabric, it makes a hub for folds.

A person and his clothing tend to move and act as one. Not only does our clothing conform to our bodies in the moment, it carries the memories of past movement. Think of the knees of your favorite jeans. That’s one reason it feels strange to borrow another person’s clothes, and why we develop old favorites we’re loath to get rid of.

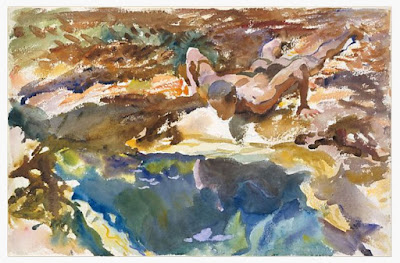

|

| This is my favorite of Albrecht Dürer’s drapery studies. Undated.

|

To draw folds accurately, you need to see them as having shape and volume. It’s useful to see each fold as having three surfaces: a top and two sides. The valley between folds is the base from which the folds arise. You may not always see both sides, because one might be folded back, but they’re always there.

It may be difficult to puzzle out whether you’re seeing the top or sides of a fold. The answer is really immaterial, as long as you’re drawing the fold as a three-dimensional object. Folds are infinitely variable, and sometimes the top will take the form of a sharp crease, or a side will disappear for a while. Even when that happens, bear in mind that you’re drawing a three-dimensional object. Folds are never simple lines drawn over the surface of fabric.

Like the rills on a hillside, folds have a way of transmogrifying into other shapes. They twist and turn and merge into other folds, or vanish entirely. It’s helpful to block out drapery as a whole before you start drawing. Just as if you were drawing a hillside, start by measuring the big shapes and checking angles.

In your first pass, don’t worry about subtleties of shading. Think of your this phase as a plan from which you’ll draw or paint. In other words, make it clear, concise, and accurate.

When you’ve finished, you can test the accuracy of your drawing by dropping a contour line across it. Imagine a bug crawling in a straight line from one side to another. Trace that line with your pencil. When your imaginary bug hits a fold, he’ll crawl into it and out the other side. If you get to a point where you can’t figure out where your bug should go, you’ve made a drawing error or been unclear. Go back and resolve that.