People do not become brave in a vacuum—they get that way by taking risks.

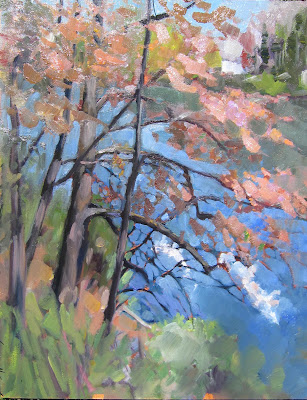

| Along the Pecos River in Winter, by Carol L. Douglas. Available. |

The newest diversion for small businessmen in America is to sit up nights and think about what they should cancel. I had my most recent conversation about this with Jane Chapinon Saturday, as we try to figure out whether my New Mexico workshop is on or not. The problem in New Mexico is the same one we faced here in Maine earlier in the year: the same advisories that are appropriate for places like Albuquerque are overkill for small mountain towns. Even though painters will be safe in Pecos, we still must abide by state law.

It may seem like tempting fate, but I don’t worry overmuch about coronavirus. It’s wise to be cautious about it, just as it’s wise to be prudent when camping in bear country. But I’m in good health for my age, and my chances of recovery are vastly greater (better than a hundred to one) than dying if I contract the disease. I’d like to live to a great old age, but, as Lucy Angkatell chirpily notes in Agatha Christie’s The Hollow, we’re all going to die of something anyway.

|

| Downdraft snow, by Carol L. Douglas |

The Hollow was written in 1946, and Lady Angkatell’s attitude toward death is as obsolete as the novel’s melodrama. Modern society is constructed around a fierce desire to minimize risk. We worry about lawsuits; we worry about perceived threats that may have little basis in reality. We’ve been conditioning ourselves out of risk-taking for most of my adult life.

When I was a kid, we routinely walked to school without adult supervision, played games without adult supervision, rode horses without adult supervision, and used tools and equipment with only the loosest adult supervision. Today, kids are barred from doing these things, yet the child mortality rate has never been lower in America (largely because of vaccines).

| New Mexico Farmstead, by Carol L. Douglas. |

When my kids were babies, the bogeyman in the room was child abduction, which kept a whole generation under the watchful eyes of their mothers. It turned out to be largely illusory, but it effectively ended childhood freedom.

Yesterday I was talking with a Zoom student from Tennessee. He mentioned that he learned to drive a tractor at age 8. Today, he’s a pilot. I was about the same age when I learned to drive our Ford 9N. By age 14, I was moving hay from fields in one town to our home farm in the next. Had I been injured in a farm accident then, it would have been a tragedy. Today, it would be a reason to pass a new set of laws barring kids from farm work.

| Pecos hillside, by Carol L. Douglas. No, our workshop isn’t scheduled for snow season; I just have a perverse liking for winter. |

But being raised as ‘free range’ children was formative to creating intrepid adults. A child who learns how to manage risk will grow into a confident adult. That’s key, as I wrote recently, to success in the arts. People do not become brave in a vacuum—they get that way by taking risks and accepting defeat.

I occasionally have a super-achiever in painting class, a person who has always been the best at whatever he or she attempts. That’s a terrible handicap in art. The inability to accept failure means they can’t accept the risk that is inherent in all art-making. Their fear of failure consigns them to fail.

Art, after all, could be defined as a series of failures on the way to an impossible objective. For that, risk-taking is a great teacher.