In a world obsessed with rawness, you could do worse than studying the Luminists.

|

|

Lumber Schooners at Evening on Penobscot Bay, 1863, Fitz Henry Lane, courtesy National Gallery of Art. The setting for this painting is, quite literally, out my back door. |

A fascination with light is something Luminism shares with Impressionism, but the path there is exactly opposite. Impressionism is what art historians call painterly—there are visible brushstrokes in the top layer. Luminism is what is called linear—modeling and distance are created with skilled drawing and brushstrokes are suppressed.

|

|

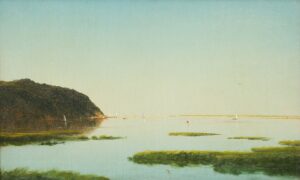

View of the Shrewsbury River, New Jersey, 1859, John Frederick Kensett, courtesy Rutgers University |

In the Luminist world, light is generally hard. The soft, ambiguous atmospherics of Claude Monetor James Abbott McNeill Whistler were inconceivable to these painters. Attention is paid to detail, which is often picked out by some larger-than-life weather event. Atmospheric perspective is exaggerated for effect.

For this reason, scenes of mountain vistas and the ocean were especially popular. They allow us to see light playing itself out in all its variations. Fitz Henry Lane was a popular painter of the Maine and Massachusetts coasts, and his work is a compendium of Luminism’s themes. There’s extensive detail, an expanse of interesting sky, and careful attention to value.

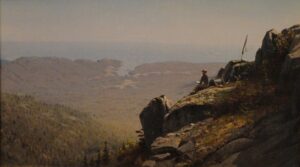

There’s often an elevated viewpoint, where we are looking down on the scene in a very personal way. It’s a viewpoint that’s not quite possible in reality. It seats us right next to God, in effect.

|

|

The Artist Sketching at Mount Desert, Maine, 1864-1865, Sanford Robinson Gifford, courtesy National Gallery of Art. |

Luminism has no meaning divorced from its themes, which were intimately related to those of the Hudson River School painters: discovery, exploration and settlement. In their telling, America is a peaceful Eden where nature and human beings coexist peacefully. The schooner rests quietly at anchor; tilled fields nestle undisturbed below the mountains; There are no blizzards, tornadoes, or wolves to disturb the balance. There is only that sublime light from the heavens.

Hudson River School artists believed that the American landscape was a reflection of God. Luminism, in particular, is connected with Transcendentalism, which saw a close link between the spiritual and physical worlds.

This has to be set against the times in which these paintings were created. It was a period of fast settlement and rapid industrialization, particularly in the east coast where these painters sold their work. Luminism was painting an America that—if it existed at all—was short-lived and vanishing.

|

|

Cotopaxi, 1862, Frederic Edwin Church, courtesy Detroit Institute of Arts. Church showed Americans the whole New World through a Luminist lens. |

At the same time, there was an intense curiosity about parts of the country that most people had never seen. That’s why tens of thousands of people were willing to pay 25¢ each to see Church’s Niagaraon exhibit. The massive, glowing canvas was a proxy trip to the Niagara Frontier. And Church could, with a flick of his brush, conveniently excise all the people who lived and worked in Niagara at the time.

The tags Hudson River School and Luminist came long after both movements had ended. They were initially dismissive. Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Abstraction had taken the western art world by storm. Careful brushwork and drawing were filed in the back of our consciousness. The cognoscenti considered them quaint. But they’ve always had their fans in Middle America.

Much can be learned from these painters in regards to light. And it hurts nobody to know how to use the brush carefully and discreetly at times, to feather, brush and model with delicacy and intention. In a world obsessed with rawness, you could do worse than studying the Luminists.