Fog has color, movement, and attitude, and is a great tool to understand atmospheric perspective.

|

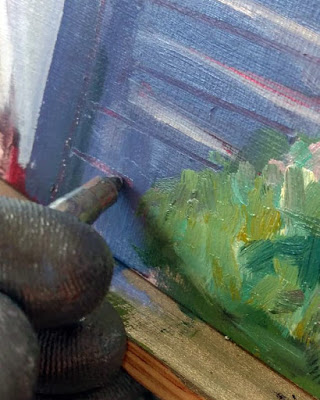

| Fog Bank, 14X18, oil on canvasboard, by Carol L. Douglas, $1275 unframed. |

I appreciate the care with which the National Weather Service makes hour-by-hour graphical forecasts. They’re the plein air painter’s best friend, since they predict not only the chance of rain, but the sky cover and the wind. However, they’re often wrong for areas near deep water. Mother Nature is impulsive and unpredictable where warm air first encounters the cold sea. Yesterday I drove to Warren, which is 12 miles to the southwest of me. I traveled through a band of dense fog, a band of brilliant blue, and ended up under a dour, dull sky.

That makes planning my plein air class a game of chance. My primary goal is to teach fundamental skills, but along with that I want my students to master every possible light situation. Yesterday’s nominal subject was value-matching and patterning. However, with a fog as rich and deep as the one we encountered at Owls Head, it seemed a pity to not concentrate on the atmospherics.

|

| Early Spring, Beech Hill, 8X10, oil on canvasboard, $522 unframed. |

Few things are more beautiful than fog—or more annoying to the painter who insists on golden sunlight in every painting. Fog has color, movement, and attitude. It’s a great tool to understand atmospheric perspective—and to teach patience with the passing scene. It moves in and out, obliterating a major compositional point here, and adding one there.

The more I teach, the more I realize how much I have to learn about teaching. My student, Jennifer Johnson is in a transitional phase where nothing she paints looks good to her. That’s painful, but it’s a sign she’s about to make a giant leap forward—if she allows it. The fainthearted painter will retreat back into the shell of the familiar. The courageous will allow herself to experience the “I hate everything I’m painting” phase and wrench forward into new discovery. Jennifer is, of course, one of the courageous.

|

| Jennifer Johnson is working her way through her period of dissatisfaction by returning to first principles. That means starting with thumbnails and gridding them onto her canvas. |

If you play a musical instrument, you’ve had the experience of mastering a piece part-by-part. You get the left hand down fine. Then you try to add the right hand, and what you’d learned in the left hand falls apart. But if you persist, your brain will integrate the two tasks. Adding new ideas to painting works the same way.

To ride through this, Jennifer has sensibly returned to first principles. One of these is thumbnails and value sketches, which are then transferred to the canvas in the form of a grisaille. Her example, above, from last week’s class, is far better than any I’ve ever made.

What I realized from watching her is how frequently students can do each step well, but not integrate them as a whole. That’s something I need to focus on more. The sense of being needed put a spring in my step. It seemed like only fifteen minutes had passed and the three-hour class was done. Rats.

|

| Frank Costantino with Ann Clowe, Nancy Lloyd and Lisa Siegrist. |

Yesterday’s students had the opportunity to watch a real watercolor master at work. My buddy Frank Costantino is in town, and they looked over his shoulder as he painted the lobster boat Daphne Lee. If he can stand more fog, we’ll go out again today.