If you have a fear-hangover from COVID, perhaps Easter is the season in which you should make a conscious choice to drop it.

Working together, our best intentions can yield some astoundingly damaging results. That, in so many ways, defines the past year. With largely good intentions, we’ve managed to significantly dent the world’s economy, infringe on personal liberties, isolate the elderly and marginalized… and still COVID marches on.

It’s been rotten for the body religious, which was already hurting. Here in America, we reached a grim milestone in 2021: fewer than half of Americans consider themselves to be members of a church, synagogue, or mosque. That’s shocking for the nation widely considered to be the most religious in the western world.

I learned this week that St. Thomas’ Episcopal Church in Rochesterwill remain shuttered for the second Easter in a row. As I wrote about galleries last week, I doubt that many institutions will survive two years of closure.

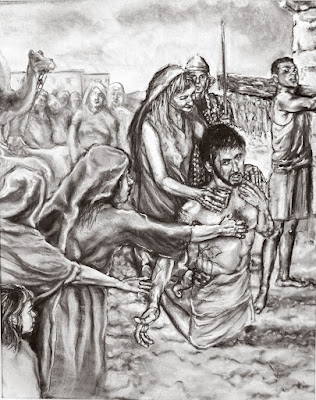

In summer, 1999, I was asked to do a set of Stations of the Cross for St. Thomas’. By that September I’d been diagnosed with colon cancer. I had four kids, ages 11 to 3. My primary goal was to stay alive long enough to see them raised.

Finishing an art project seemed frivolous, and darned near impossible. I was especially disinterested in one that dealt with the violence leading up to the crucifixion. The following year was a late Easter, so by the time Holy Week arrived, I had a rough version finished.

I drew in my hospital bed, from my couch, during chemotherapy. I wasn’t at all engaged or enthused. When I was well enough, I arranged a massive photoshoot and took reference photos. The final drawings were finished two years later. They weren’t my best work, but at least they were done.

And yet, they’ve been in use for two decades. Every Holy Week, I got notes from a parishioner telling me how much they appreciated them. I’ve certainly gotten more meaningful mail about them than any other work of art I’ve ever done.

Except last year. Last Easter, the churches of America were closed. Their people observed the rites from afar. That was appropriate then, but we’ve lived out our penance for a year now. It’s almost unbelievable that the faithful among us don’t see the urgent necessity of gathering together to celebrate the risen Lord, this year of all years.

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves. Today is Good Friday. It commemorates Jesus taking the punishment intended for all mankind’s sin onto his own, all-too-human, body. It culminates in death and hopelessness. That’s what the Stations of the Cross are about, whether they’re in the Catholic, Episcopal or any other tradition.

Are you still afraid to go to church on Sunday? It’s hard to reconcile that with the promise of eternal life that Easter represents.

I’ve traveled as much this year as any year. I’ve taken sensible precautions, including at least a dozen COVID tests, all of which were negative. Although I have the same fears and griefs as anyone else, there’s a part of me that’s simply not afraid. I respect death; heaven knows I’ve seen enough of it. I have lost people I love to COVID. But I choose life.

Fear is a prison, a mighty weight, and the brake that stops all forward motion. If you’ve been left with a fear-hangover from COVID, perhaps Easter is the season in which you should make a conscious choice to drop it.

The Stations can be walked virtually here: