What is art? What is illustration? Does it matter?

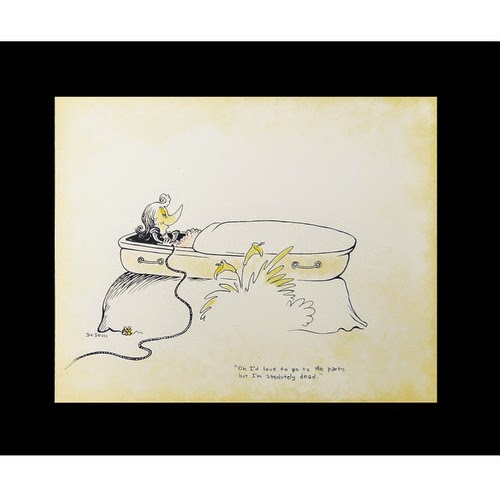

| Trick-or-Treat! From my brief period illustrating; prints available (DM me). |

“I am trying to understand the difference between a painter and an illustrator,” writes a reader.

Paint is a just a medium. You can use it to illustrate, or you can hurl it in meaningless patterns. Conversely, you can illustrate with any two-dimensional medium, including pencils, ink, photography or cut paper. The difference is in intent.

An illustration is usually a visual accompaniment to a text. However, that’s not always true. There are illustrated books (Albrecht Dürer’s Passions, for example) that do not need words at all. There are many children’s books with no words. In fact, one could argue that all of western religious art is illustration. The text (the Bible) was just not written down. Either the intended audience was illiterate or they all knew the story anyway.

| Gas Station, by Carol L. Douglas. From my brief period illustrating; prints available, DM me. |

Illustrators are usually hired by writers or publishers. The work is limited in scope and concrete in character. Fine artists have no middleman between them and the market. They can be as obscure as they wish. But fine artists certainly work on commission, and illustrators often work on spec, so even that distinction is hazy.

There was a time when this question mattered to me. I was trying to make the jump between graphic design and painting full time. I did it by writing and illustrating two books. We are all born with an innate ability to imagine pictures, but I’d disciplined my artistic sensibilities to be subservient to the client. It took these stories for me to loosen up and find my focus. It’s never been a problem since.

| Girl in Closet, by Carol L. Douglas. From my brief period illustrating; prints available, DM me. |

But there’s an insidious way in which this question is sometimes asked. What’s implied is that fine art is somehow better than other forms of artistic expression.

Yes, illustration is a fine craft rather than a fine art. Like tapestry, jewelry, carving, etc., illustration has a practical purpose aside from beauty. Paintings have none, unless you’re using them to plug holes in the wall. If you want to know if you’re an artist or craftsman, ask yourself if your finished product has any tangible purpose. If it’s useless, you’ll know you’re an artist.

The problem lies in assuming that either one is more important than the other. Our modern viewpoint comes from the 19th century Cult of Genius, which mistakenly put fine artists in the category of intellectuals instead of tradesmen.

| Kitchen Table, by Carol L. Douglas. From my brief period illustrating; prints available, DM me. |

This is why plein air painting gets so little respect, by the way. It rejects the idea that fine art is primarily an intellectual activity. Instead of making great statements, plein air painting has a lowly and practical view of the world. It seeks to make pictures that make people happy.

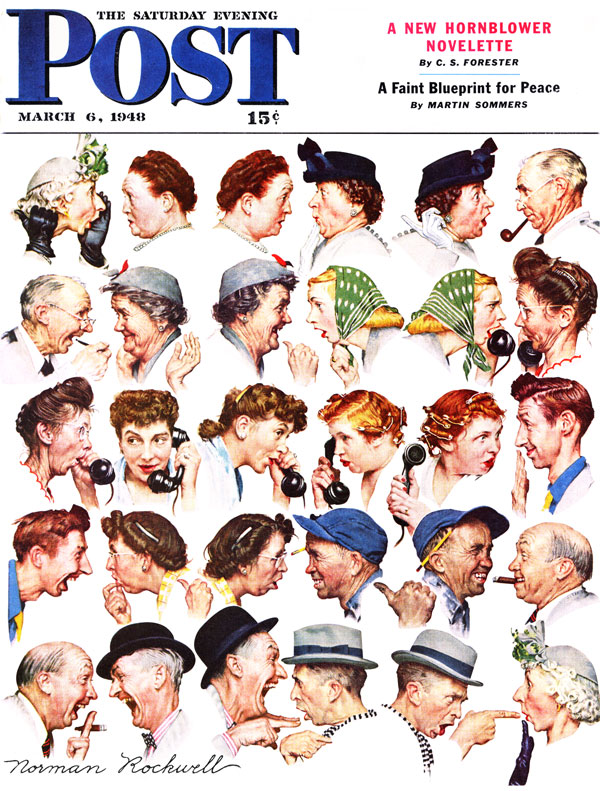

There’s never been any distinction between fine art and illustration in terms of quality. If there ever was a gap, it was bridged long ago, starting with the unknown monks who illuminated books before the printing press was invented.

With the advent of industrialization, individuality and beauty was stripped from the objects we use every day. Brilliant craftsmen-artists like William Morris, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Margaret Macdonald, and the Roycroft Movementclosed the gap between art and function once again. And who in this world would argue that N.C. Wyeth and his peers of the Golden Age of Illustration are not among the world’s greatest artists?