We’re products of our times, which are shifting rapidly. Why not cross the direct-indirect painting line and see if the other side speaks to you?

There is nothing inherently wrong with indirect painting; it’s how I initially learned. Indirect painting is useful in portraiture, still-life, or the big tableaux of Peter Paul Rubens. It’s less useful in plein air because it’s so slow. Moreover, the same dark shadows that are mesmerizing in Rembrandt’s self-portraits can be stultifying in landscape.

In every medium, the major division in technique is between direct and indirect painting, although that line is porous. Modern alla prima oil painters still lay out their paintings as a grisaille; we work thin in the underpainting, reserving thicker paint for the top layers. Except in plein air, few of us are fast enough to finish a painting entirely wet-on-wet. We sometimes glaze to correct color or deepen shadows. Conversely, masters of the Renaissance like Jan van Eyck Rogier van der Weyden and Rembrandt used wet-on-wet passages in their paintings. Frans Hals worked almost entirely alla prima.

|

|

Study of clouds above a wide landscape, 1830, John Constable, is an example of a transparent watercolor. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum. |

In direct painting, the artist attempts to hit the proper color (hue, saturation and value) on the first stroke. We sometimes call this alla prima or au premier coup. Regardless of the name, the goal is minimal modification and correction, leading to fresh, open brushwork. That’s true in oils, watercolor and acrylics.

Direct painting is largely the legacy of the 19th century, facilitated by a dizzying array of factors including paint tubes, railroads, modern chemistry, and the mindset of the Impressionists. Modern chemistry also brought us alkyd and acrylic paints. These are tailor-made for indirect painting, but the technique still sits on the sidelines. That’s largely because of our collective temperament.

Indirect painting is done with multiple thin layers of paint. Each subsequent layer is intended to modulate, rather than cover, what’s below. These layers usually dry between coats, but not always; you can achieve remarkable effects by painting into wet transparent passages with opaque paint. But in general, indirect oil painters start with a dark transparent layer, followed by a middle layer of opaque color. These are allowed to dry and the final modulation of color is done by glazing thin layers of color on top. At the very end, the artist will add highlights and opaque or semi-opaque scumbling in some passages. The contrast between opacity and transparency can be very beautiful.

|

|

Self portrait, 1659, Rembrandt, courtesy National Gallery of Art, is an example of indirect oil painting. |

In watercolor, the order of operations is somewhat reversed: traditionally, watercolor starts with light glazes and then adds darks at the end. But watercolor need not be applied in a series of discreet glazes any more than oils must be.

Glazing, however, allows the artist to work thin, slowly, and thoughtfully. Indirect painting allows for meticulous detail that can never be achieved in direct painting.

A glaze is just a thin, transparent layer of paint. It gets thinned with medium (oil) in oil painting, with water in watercolors, and with a combination of water and medium in acrylics. It’s hardly worth taking a class to learn to do it, although I can certainly show you. Here are the general rules:

- The fat-over-lean rule is imperative in solid media. Scale up the amount of medium in each successive layer, and keep it as lean as you can;

- Glazing works best with transparent pigments;

- If you must glaze with white, use zinc white instead of titanium (and it’s the only application for zinc white in oil painting);

- Glazing over impasto gives you a very irregular finish. Unless that’s your goal, avoid it.

In good glazing, light is able to bounce back from whatever is below the surface—the substrate or opaque layer in oils and acrylics, or the paper in watercolor. That’s why opaque pigments—especially titanium white—don’t work well. What remains visible at the end is a combination of all the layers. The colors in all layers appear to mix, although they are, in fact, physically separate.

|

|

Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909, George Bellows, courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art, shows the immediacy and power of direct painting. |

Mainstream oil painters have been painting directly for nearly 150 years. Mainstream watercolor painters, on the other hand, sometimes seem stuck in a sea of indirect glazes. We’re in a rapidly-shifting period in history. Why not experiment with the other side and see if it speaks to you?

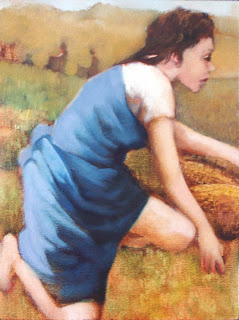

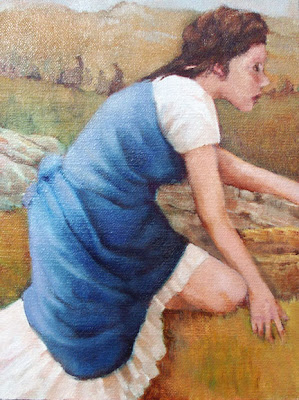

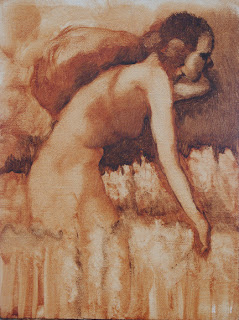

During Wednesday’s class I demonstrated a method of indirect painting where one starts with a monochromatic

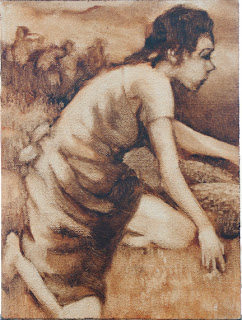

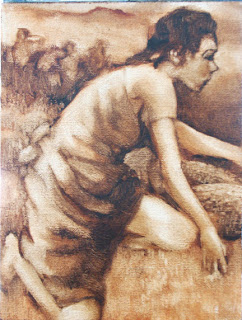

During Wednesday’s class I demonstrated a method of indirect painting where one starts with a monochromatic  While the first drawing was a sensitive rendering, it is a static composition, completely in profile. So I wiped it out and redrew it. The second draft is a rather brutish woman, but I liked the pose.

While the first drawing was a sensitive rendering, it is a static composition, completely in profile. So I wiped it out and redrew it. The second draft is a rather brutish woman, but I liked the pose.

I chose a transparent palette with mainly 20th century pigments: chromatic black, phthalo emerald, hansa yellow, Indian yellow, napthol red, quinacridone violet, ultramarine and phthalo blue. I chose this palette based on personal preference, because it certainly isn’t historically correct. Since the 20th century pigments were developed for direct painting, the end result is kind of quirky.

I chose a transparent palette with mainly 20th century pigments: chromatic black, phthalo emerald, hansa yellow, Indian yellow, napthol red, quinacridone violet, ultramarine and phthalo blue. I chose this palette based on personal preference, because it certainly isn’t historically correct. Since the 20th century pigments were developed for direct painting, the end result is kind of quirky.