The greatest landscape artist of the 19th century wasn’t a Frenchman. He was Hiroshige, or so his western contemporaries thought.

|

|

Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge At Atake, 1856, Hiroshige.

|

As I was walking to the post office yesterday, a miniscule rain shower spattered in the woods next to me. It lasted no more than a second. Being modern, I didn’t recognize it as an omen. Despite the forecast, by midafternoon it was misting heavily enough that no outdoor painting was possible.

We’ve had a lot of rain this spring in the northeast. The St. Lawrence River is full, so they’re holding water back in Lake Ontario, which is in turn flooding parts of Toronto and Rochester. Here in Maine the creeks and rivers patter loudly and joyfully down to the sea. And still it continues to rain; it’s on the forecast for the rest of this week.

|

|

Night Rain On Karasaki, Hiroshige

|

The 19th century Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige often used mist and rain as motifs in his compositions. He worked in a genre called ukiyo-e, which translates as “pictures of the floating world.” After Commodore Perry forced Japan opento Westerners in 1854, ukiyo-e was exported to the west. It had a profound influence on Western painting.

Hiroshige was the last master of ukiyo-e. Born in 1797 in Edo (Tokyo), he was left orphaned at the age of 12. His father was the samurai fire fighter of Edo Castle, and this responsibility passed to the son. Although he went on to study and work full time as an artist,he never shirked his duty, eventually passing it along through his family.

|

|

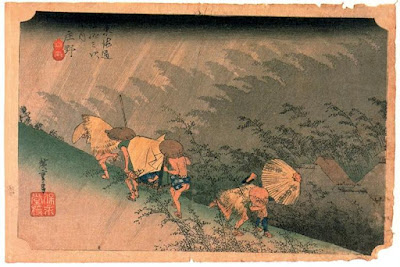

Two Men On A Sloping Road In The Rain, Hiroshige

|

Shortly after his parents’ deaths, he began studying art with the master Utagawa Toyohiroof the Utagawa school. This exposed him to western ideas of perspective, which had been imported in books carried to Japan by Dutch traders. The Utagawa school pioneered landscape painting as an independent genre.

Hiroshage worked with a sketchbook, traveling to other locations to assemble ideas and motifs for his woodcuts. Although he was prolific and famous, he was never wealthy; at one point his wife had to sell clothing and ornamental combs to support his work.

|

|

White Rain, Shono, 1833-34, Hiroshige

|

Hiroshage worked within the narrow genre of meisho-e, or “pictures of famous places.” In a sense, these were the predecessors of picture postcards.

Japonisme took the 19th century world by storm after the International Exposition of 1867 in Paris. Oriental bric-a-brac poured into western Europe. James Whistler reportedly discovered Japanese prints in a tea room near London Bridge. Claude Monet saw them used as wrapping paper. James Tissot and Edgar Degas collected ukiyo-e. Mary Cassatt was an open and avid admirer and imitator of the style. Vincent van Gogh famously copied two of the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, which were among his collection of ukiyo-e prints.

And it wasn’t just the visual arts. Gilbert and Sullivan produced their comic masterpiece, The Mikado, in 1885. Japanese gardens became the rage. By the end of the century, Hiroshige was being referred to as the greatest painter of landscapes of the 19th century.

|

|

Evening Shower At Nihonbashi Bridge, 1832, Hiroshige

|

Hiroshige died at the age of 62 during a cholera epidemic in Edo. Just before his death, he wrote:

I leave my brush in the East

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land.

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land.

Sadly, the same cultural exchange that sparked so much artistic development in Europe also spelled the end of ukiyo-e. The rapid Westernization following the Meiji Restoration found photography vying with traditional woodblock printing. By the 1890s the tradition was, more or less, dead.