What paintings make the final cut? How about choosing by committee?

|

|

El camino hacia el pueblo, by Carol L. Douglas

|

Keith Linwood Stover once asked me why artists seek criticism in the first place. “We’re not the best judges of our own work,” I told him. (This is why gallerists and curators are such important players in the art process.) That’s especially true when you’ve just painted for a week in an alien environment. Whatever judgment you have goes to pieces.

I’m not alone in finding this difficult. Last night I sat around the table at Jane Chapin’s house with a group of artists, debating what we’ll submit. Richard Abraham and I are in the same position: our strongest works are in a sense, redundant. They’re each of the same subject. This makes us both a little nervous.

|

|

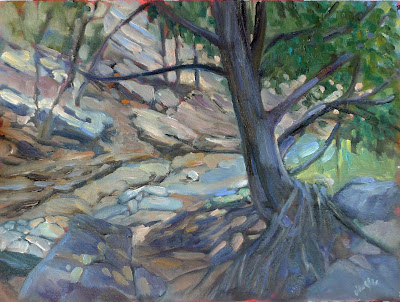

Dry wash, by Carol L. Douglas

|

I looked at his three top contenders and gave an opinion; he looked at my three and gave an opinion, and it was unsettling, because he counted back in a painting (Dry Wash) that I’d already eliminated. Men and women approach paintings differently, and understanding how the male mind works might be helpful in jurying.

My opinion is that any of Richard’s three contenders will win him a prize. His options are all good. That makes me wonder if I’m dithering over equally inconsequential differences. Still, the choice of submissions is the most difficult job of the week, and it behooves us to take it seriously.

|

|

La casa de los abuelitos, by Carol L. Douglas

|

A painting should be—as the old saw goes—compelling at 300 feet, 30 feet, and three feet. The first question, then, is what will draw someone from the other side of the room. To answer that definitively, I’d have to be inside the head of the juror (Stephen Day) and I’m not. Looking at his work only tells me so much. I can’t know what his goals are, how his day is going, or any of the other myriad thoughts that go into his decision.

|

Hoodoos in training, by Carol L. Douglas

|

Why do I distrust my judgment? I’m always most intrigued by the paintings that are terrifically difficult to master. That’s why I love Jonathan Submarining, from Castine 2016. The viewer may just see a Castine Class sailing school bobbing around on the waves, but I see a tough painting done knee deep in the surf and executed well.

This is true too with Dry Wash. The only reason I might change my mind at the last minute is that the dappled light and rocks are well-executed. But the other two better meet the 300-feet challenge.

|

Castigando del caballo muerto, by Carol L. Douglas

|

That puts me in a quandary. I’ve written before about who I trust to critique my work. I messaged images to two people yesterday: my husband and Bobbi Heath. Their opinion was consistent (and it matched, for the record, Jane Chapin’s).

But in the end the decision rests with me, and it’s no fun.