I don’t want painting students to pass a test before they start with me; I just want them to be able to thread their metaphorical sewing machine on their own.

| Midsummer, 24×36, $3985 framed. In honor of Canadian Thanksgiving, which is Monday, let’s feature paintings I’ve done in Canada. |

As soon as I announced that I wasn’t taking beginners anymore, a number of my students expressed trepidation about continuing with me. “But I’m a beginner!” they said. In some cases, they’re right, but they’re already on the path to understanding painting. In other cases, they don’t have a clue how well they’re painting, and how much they’ve learned.

When I said ‘beginning painters,’ I meant people on their first date with a brush. They’re unclear on the materials and what they’re used for. They’ve never mixed paint or handled a brush. They’ve never heard or considered basic terms like hue, saturation or value.

Anyone who’s taken one of my classes is past this newbie-phase, by definition. And anyone who’s studied with another teacher or taught themselves with the aid of books or videos is unlikely to be a beginner, either.

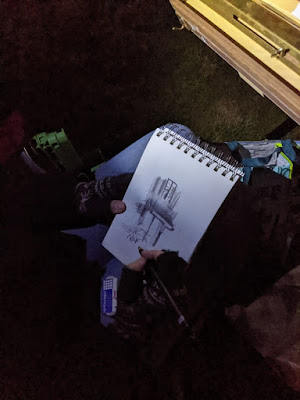

| Ottawa House, 16X20, oil on canvas, $2029 framed. All these paintings were done en plein air. |

My friend and student Jennifer Johnson—who taught quilting for many years—says that she would have students in her classes with advanced design skills, and others who’d never threaded a sewing machine before. “Neither of these things are more important than the other,” she said. “But I spent 90% of my time rethreading the machine for the beginner.”

I’m trying to describe something analogous in paint. I don’t want painting students to pass a test before they start with me; I just want them to be able to thread their metaphorical sewing machine on their own.

In fact, I think it’s important to have a class of different levels. Hearing the steps justified and explained to a less-experienced painter is often helpful to the more-experienced painter. Sometimes, an essential principle hasn’t really clicked. Or, our willful brains just forget something important.

|

| Clouds over Teslin Lake, Yukon Territory, 8×10, oil on canvasboard, $522 unframed. |

As with every discipline, painters improve at different rates. How fast they learn depends on their natural quickness, how much time they can practice outside of class, distractions, anxieties, and other factors. I could start twelve painters at exactly the same level, teach them the same lessons for a year, and there’d still be a wide range of achievement at the end. That’s natural, and if you’re someone who learns more slowly, it’s nothing to worry about.

The greatest painting classes are marked by camaraderie and good will. The best way to learn something is to explain it to someone else. Those painters generous with their own knowledge are helping themselves as much as they’re helping their friend.

|

|

Cobequid Bay farm, oil on canvasboard, 6X8, $348 unframed. |

Having said all that, Bobbi Heath tells me she has run up against a problem and will not be offering her introductory oil-painting class this fall. That means that for the short term, new oil painters will still be coming to me (subject to space limits in my classes, of course). Cassie Sano will still be offering introductory watercolor classes, concurrent with my own fall classes.