A good painting requires a good plan. What does that mean?

This last weekend I was painting in the 14thannual Paint for Preservation for the Cape Elizabeth Land Trust. This always involves a big canvas, and this year was no exception: I painted 30×40.

I always start with a drawing in my sketchbook; when I’m working this large, the drawing becomes paramount. To look at my canvas from a distance meant climbing down into a small ravine and back up the next finger of rock, so I didn’t do it often. Accuracy in that situation requires planning. I transfer the drawing faithfully to my canvas, gridding if necessary. Then the sketchbook lies at my feet so I can consult it for values if necessary.

|

| Foghorn Symphony, 36×40, by Carol L. Douglas, will be available through the Cape Elizabeth Land Trust in late August. |

“You write numbers on it?” said Ken DeWaard, who’d stopped by with his morning coffee.

“Numbers and colors,” I said. That’s not my idea; it’s one I stole from an old guy named Vincent van Gogh, who often wrote the colors alongside his sketches. The sun at dawn on Saturday was a lemony yellow, and it would have been easy to remember it as richer and deeper. That would have overridden the sense of a transient sea-fog in the distance, which was causing the five lighthouses of greater Portland to play a fog-horn symphony.

Plein air events like Paint for Preservation have no do-overs. We’re required to put out a good painting. There are two options. You can paint more than one, and choose the best. That seldom works for me, since I’m no judge of my own work in the thrust-and-flow of an event. It’s also a lot of work.

|

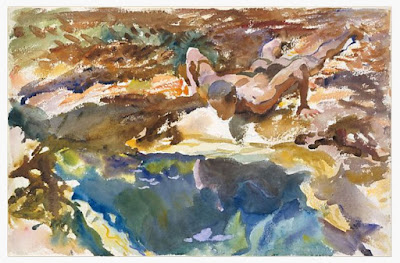

| Zeb Cove, 40×40, was my 2020 painting for CELT’s Paint for Preservation. |

.

I go with the second, which is to paint one good one from the start, using all the tools at my disposal. Since a painting always goes wrong in the planning stages, I make sure my plan is solid, and then I stick with it.

What makes a good plan?

Precision of drawing

This means proper perspective and measurement. You might think this is irrelevant when the subject is rocks and the sea, but it’s as important there as with architecture. Drawing is the only clue about the distances involved. There’s a contemporary Maine style, which involves fast, loose brushwork, but it rests on a foundation of perfect drafting. In fact, bad initial drawing is a great way to end up with a tight painting, since you’ll constantly have to redraw with your brush.

|

| Four Ducks, 30×40, was my 2019 painting for CELT’s Paint for Preservation. |

Precision of composition

This means understanding the motive line, energy, and value structure of your painting from the beginning. A 30×40 painting will take from 8-12 hours to finish. The tide will have gone through one full cycle, and the sun will beat its way across the sky as you’re painting. In order to retain the light structure you started with, you must lay it out in advance—and then you must stick with it.

Precision of color

Nothing makes for a muddier painting than constantly restating colors because you didn’t get them right on the first try. Make a grisaille, and check your mixed colors against it.

|

| Rocky, 36×36, was my 2018 painting for CELT’s Paint for Preservation. I’m detecting a theme here. |

To mix color properly, you must be absolutely conversant with the pigments on your own palette. This requires practice. The goal is au premier coup, or to nail it on the first strike. That goes not just the for darks, but every color in the picture. Even a painting with wonderful shadows and lights will have many middle tones, often closely related in value. These are actually the most difficult colors to mix accurately. If you have a painting that isn’t working, ask yourself if it has a full tonal range, or is it simply hitting the highs and lows.