Is your painting led by your subconscious or your analytical brain? Both are important.

|

| Christmas Eve, by Carol L. Douglas |

Rebecca is a friend and very-occasional student. Yesterday she lamented that an object in a painting had changed size as she worked on it. “Maybe it’s fine to look at, but it really bothers me about my skillset, that I can’t keep things proportional,” she said. From a distance of more than 2000 miles, it was easy for me to see that she had overwritten her underpainting as she proceeded.

Perhaps a more detailed drawing to start would give her some lines to color in, I suggested.

“I’m trying so hard not to go there right now, but point taken. I definitely did give up on drawing the truck, as it was getting truly awful, and just left it for the paint to make sense of,” she responded.

|

| School bus, by Carol L. Douglas |

I understand this problem; it’s why my sail in my current nocturne keeps kissing the edge of the canvas even as I use a ruler to try to force it across the edge. That, too, started life as a very loose exercise; heck, the boat has already been three different places on the canvas.

Either we draw carefully and discipline our hands to our brain, or we let our subconscious rip and deal with what it hands out. Clearly Rebecca’s subconscious mind thought smaller was better for that truck. Looking at it in relation to its setting, I think her subconscious mind was being more artistic than the bald truth of her reference photo. By making the truck smaller, the painting had room to state a universal revelation: the sea is so great and my boat is so small.

The subconscious has been a big deal in painting ever since the Surrealists became interested in the probing of Sigmund Freud and his fellow psychoanalysts. The Surrealists were not just interested in exploring the relationship between the conscious and self-conscious; they wanted to see rationalism overthrown, both personally and socially. They believed that art that comes from our subconscious is more powerful and authentic than the products of our conscious, analytical, minds.

|

| Christmas night, by Carol L. Douglas |

That made them try all kinds of games to draw the subconscious to the fore: automatic writing, dream interpretation, free association, and a kicky 1920s parlor game called Exquisite Corpse. But the subconscious is designed to run in the background. The Surrealists who continue to have the greatest influence today are those who also spent the time to analytically master their craft: Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí, and Alberto Giacometti.

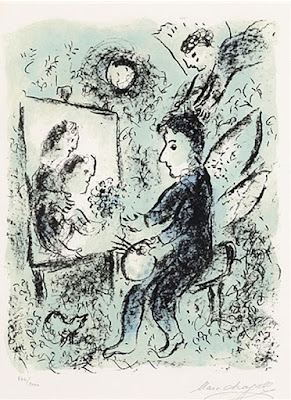

Perhaps the greatest artist to marry subconscious imagery to painting was Marc Chagall. His was a world of ghostly floating figures, scale inversions, transparent wombs, and animal/human hybrids. They are not his individual dreams, but the collective imagery of a people. Chagall painted through the bitterest years for European Jews in modern times, but his canvases are not terribly frightening. He didn’t give in to night terrors.

|

| A demo painting for the Bangor Art Society. |

The problem with our inner mind is that most of us don’t like it that much. That’s why we’re constantly trying to blot out our brushwork and trying to school our shapes into photographic conventionality.

I sometimes amuse myself by painting landscape from abstraction, which is a loose form of automatic writing. In fact, all of the paintings illustrating this post were done with no reference. It’s a rebellion against literalism, an attempt to push my analytical mind back a bit before it crowds my soul out entirely.