| Peppers, by me. Cool light, warm shadows. |

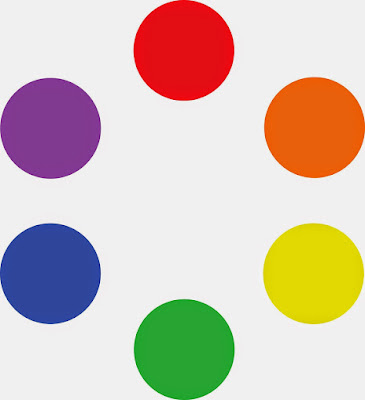

Start with an organized palette. I paint with my pigments moving from blues on the left through reds and yellows, followed by the three earth pigments to the far right. White is at the bottom. My particular system isn’t what’s important. But always put paints in some kind of logical order and in the same spot.

These basic rules make mixing easier:

- Never try to paint with hardened paints;

- Squeeze out enough paint;

- Put out every color, regardless of what you think you’ll need. Every painting should have a broad range of colors in it, regardless of the subject;

- Put out more of each color when you use it up, not when you think you’ll need it again;

- Start mixing each color with the closest match on your palette, and adjust from there;

- Add small amounts of paint as you adjust the mixture.

|

| Jamie Williams Grossman‘s lovely painting and palette in the Hudson Valley style, showing color strings. Photo courtesy of the artist. |

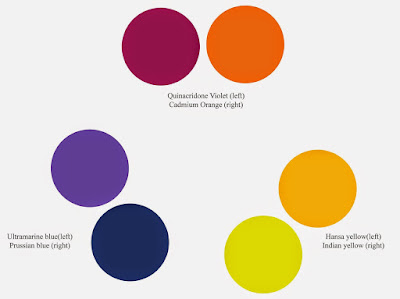

I use a simpler variation of that idea. I make mid-tone tints of each pigment. Different pigments may look the same when squeezed out of the tube, but there the similarity ends. Knowing how a pigment works when tinted with white is critical. Moreover, these tints become the backbone of a bright finished painting.

|

| A matrix is a color string in 3-D. |

In watercolor, the equivalent is tonal steps, or how the pigment acts in different dilutions. You can’t premix them, but you should understand them.

Before you lift a brush, premix three colors for each major object:

- A light tone, the color of the lightest side of the object;

- A mid-tone, which is the local color of the object;

- A dark tone, which is the deepest color.

These should be fairly close in value. For the extremes, you’ll use your global shadow and highlight colors.

In the example at top of the page, the light is cool—you can tell by looking at the tray. There is a warm dark shadow, a ‘true’ mid-tone, and a cool light color for each pepper. The tray is black. Since the shadows are warm, they’re a reddish black. They were made by tempering burnt sienna with ultramarine blue. The highlights are pale blue.

Start by getting the value right first. That’s usually the most difficult part. You can’t raise the chroma of a paint, so if you get it too neutral, set it aside and start again. If it’s too intense, mix in a bit of its complement.

|

| My palette, diagrammed by Victoria Brzustowicz. I generally don’t use red in landscape painting. |

Black has a role in painting, but it’s not in making grey. If you need grey, make one by mixing two complements. Greys are never totally neutral in real life; they always have overtones of color. Start by figuring out what that is. Then start from that color, and add its complement until you hit the perfect neutral note.

Once you’ve mixed your color ‘puddles’, look at them as a whole. How do they go together? Which do you want to emphasize?

| Keuka Lake, by Carol L. Douglas. Available. |

I use a green matrix for painting foliage. Otherwise, greens can be oppressively monochromatic in high summer. Remember those tints I had you mix? You can use them to modulate these greens into hundreds of different shades. Just use blues and violet tints to drive the greens back in space, and yellows and oranges to bring them forward.

By thinking through color relationships before you start painting, you can keep them consistent and unified. As time goes by, you’ll learn to do this intuitively. However, when I muck up a painting, it’s almost always because I haven’t really thought the light a

This was originally posted in 2020.