|

|

The Death of Marat, 1793, by Jacques-Louis David, is imbued with both emotional connection and revolutionary fervor.

|

Jacques-Louis David was not merely a painter; he was, above all, a revolutionary. Moreover, he had perfect pitch for the sentiments of the age.

In the 1780s, as French opinion stiffened against the Ancien Régime, David was painting severe neoclassical history paintings in reaction to the Rococo fantasies of the monarchy. His pen-and-ink-drawing, The Oath of the Tennis Court (1791) was an attempt to turn those history-painting skills toward the current crisis.

|

| The Oath of the Tennis Court, 1791, was David’s portrait of the formation of the National Assembly. It brought him to the attention of the Jacobins. |

This work brought him to the attention of Robespierre and his fellow Jacobins. (As a member of the Committee of General Security, David was directly involved in the Reign of Terror.) On July 13, 1793, David’s friend, the journalist and politician Jean-Paul Marat, was assassinated by Charlotte Corday. The Death of Marat is David’s most celebrated painting, and for good reason: it vibrates with personal feeling rather than intellectual ideals.

|

|

Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon I and Coronation of the Empress Josephine in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on 2 December 1804, 1805-07, Jacques-Louis David.

|

David admired Napoleon’s classical features and Napoleon esteemed David’s skill. This led to a remarkable series of portraits of the Emperor—Napoleon crossing the Alps on a fiery steed (he had, in fact, ridden a mule), Napoleon crowned in Notre-Dame, Napoleon up all night in his study, writing the Code Napoleon.

|

|

General Étienne-Maurice Gérard, 1816, by Jacques-Louis David. At the time, both painter and subject were exiles in Brussels.

|

Following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, David, a convicted regicide, fled to Brussels. There he painted his fellow exile, General Étienne Maurice Gérard. Again, David shifted to meet the times. The overblown allusions and antique coloring of his revolutionary period are gone; now he examines his subject with a deepened sense of realism.

Although the enormous social changes wrought by the American and French Revolutions could not be entirely undone, the powers that defeated Napoleon wished, as much as was possible, to return Europe to its prerevolutionary dynastic structure.

|

|

The Eltz Family, 1835, by Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, is set in front of the Alpine village in which Dr. Eltz had recently built a house.

|

One genie that couldn’t be put back in the bottle was the rising middle class. They were not particularly interested in aping their betters’ mania for classical allusion. Nor were they interested in the emotionalism of the Romantic portrait. Rather, they went for what the newly-wealthy have always wanted—a display of their economic success in a swirl of clothing and furnishings.

|

|

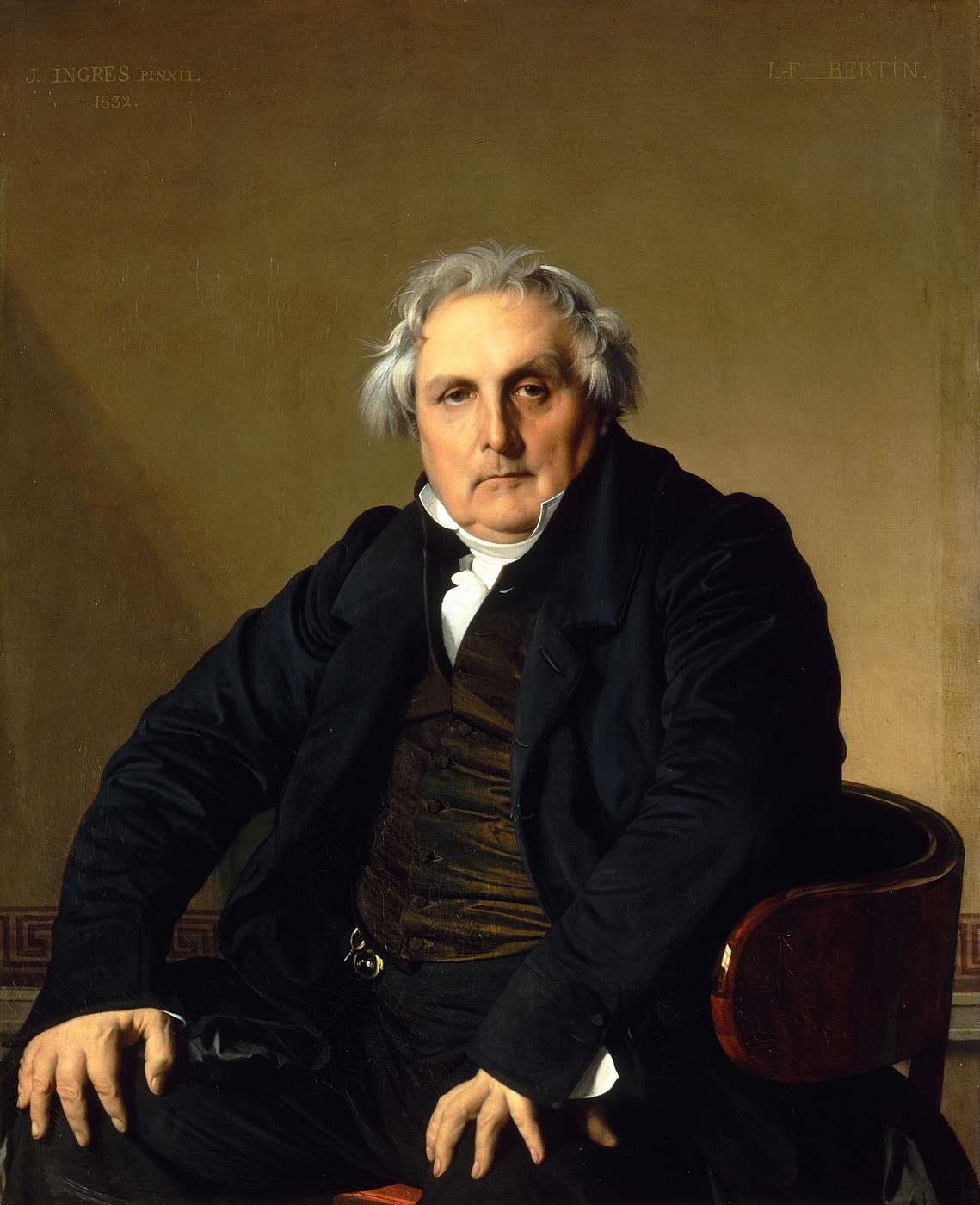

Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832, by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. M. Bertin was a respected upper-middle-class man of commerce and letters in the restored French monarchy.

|

This week I considered new forms portrait painting that reached maturity during the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment. These posts are based closely on the Royal Academy of Art’s 2007 show, Citizens and Kings: Portraits in the Age of Revolution, 1760-1830.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

.jpg)