Forget the fairy-lights; a good nocturne follows the same rules as any good painting.

|

| Hunter’s Supper, c. 1909, Frederic Remington, courtesy National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum |

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the night was a more powerful force than it is today. It’s no surprise that nocturnes have always had a place in art. Giotto’s The Kiss of Judas (c. 1304) is an early example. By the 15thcentury it was a tradition to set the Nativity and Annunciation to the Shepherds as night scenes, pitting the Light of the World against darkness for dramatic effect.

|

|

Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, 1874, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, courtesy Detroit Institute of Art |

The 17th century brought us chiaroscuro, tenebrism and three great interpreters of darkness: Rembrandt van Rijn, Georges de La Tour, and Caravaggio. In modern terms, most of their paintings aren’t considered nocturnes, because they’re set indoors. But they are nocturnes in spirit. Darkness is palpable and part of the message; it sits in counterpoint to the main theme.

It wasn’t until landscape painting came into its own that we started to see the development of true nocturnes under Whistler’s definition. Ironically, artificial light played a big part in this; it made it possible to paint at night.

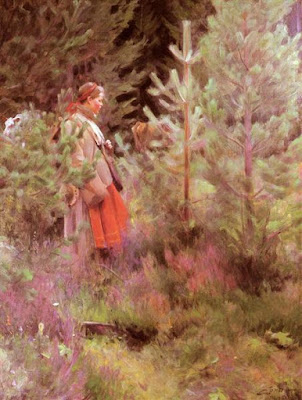

Nocturnes are particularly associated with Tonalism, which eschewed the bright colors of Impressionism and Post-Impressionismin favor of neutral colors, diffused light, and soft outlines, all of which naturally suggest low-light situations.

Frederic Remington did about 70 paintings which we might properly call nocturnes before his premature death at age 48. He was very scientific and technical in his approach, which is no surprise for an artist who started as an illustrator.

|

|

Nocturne, c. 1914, Tom Thomson, courtesy Art Gallery of Windsor |

Remington’s nocturnes are filled with color and light. Their composition is complex, often involving a foreground figure in silhouette, setting off the light source. He experimented with electric lighting and flash photography to make his paintings. That’s ironic in that they’re an elegy for the rapidly-disappearing pre-technological way of life. If you’re interested in the nocturne, the National Gallery’s The Color of Night is an excellent reference book.

Study Remington’s compositions; they’re energetic and well-realized. Too many nocturnes rest on the time-worn device of reflected light. These can be part of a great painting but they won’t carry the whole construction. A good nocturne follows the same rules as any good painting: it rests on a solid composition, it has an integrated color scheme, and its brushwork engages the viewer. If you don’t have those three things, go back to the drawing board.

Painting nocturnes en plein air requires a light. I have a cheap battery-operated book light; other artists use head lamps. The level of illumination should be kept as low as possible so that you don’t blind yourself to what you’re seeing.

|

|

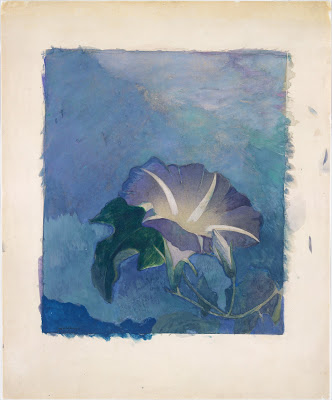

Nocturne, c. 1885, watercolor, John La Farge, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Plein air nocturnes are especially difficult in watercolor. Night air is damp, so paper doesn’t dry well (or at all). Watercolor is simply not designed for large masses of opaque darkness. Sometimes artists use ink instead of watercolor in the darkest passages; I’ve tried it and find it deadens the painting. In general, I’d suggest the watercolor artist start by drawing and move over to paint in the studio.

However, the above painting by John LaFarge suggests a workaround. He uses a medium blue in the place of black, and the viewer’s mind makes the substitution. It’s transparent enough that it would dry in the night air. A nocturne need not always be about the dead of night; it can be of twilight and dawn, too.

Regular readers know that I’m no longer taking beginning students, except in my boat workshops. Bobbi Heath is offering classes to new students in oils, and Cassie Sano has started her first session with watercolor (to rave reviews, I might add)

Bobbi’s classes are pre-recorded so students can go at their own pace. I am intimately familiar with her teaching style and material and know that you will be ready to paint with me when you’ve finished her program.

You can learn more here.

Granite State Gallery: New Hampshire Art and Artists through the Years will look at the history of New Hampshire’s native painters and visitors. It’s tonight at 6 PM, which means I can’t watch it live, so I sure hope they record it.