Some have a germ of truth; some are out and out wrong.

|

|

Île d’Orléans waterfront farm, by Carol L. Douglas. ‘Immediate’ shouldn’t mean half-baked.

|

Don’t overwork it:This is the most common bromide I hear. I hate it. It encourages painters to stop prematurely, and to not work out the latent potential or problems in the work.

It’s far better to go too far and need to fix your mistakes than never understand your limits or see where you might end up. “Don’t overwork it” is a great way to permanently stunt your growth as a painter.

Replace it with this: “If you can paint it once, you can paint it 1000 times.” It liberates you to scrape out, redraw, paint over, scribe across your surface and otherwise really explore your medium. And it’s actually true.

|

| Cirrus clouds at Olana, by Carol L. Douglas. I couldn’t have painted this had I not learned how to marry edges. |

That’s your style: When I was a painting student, I had a teacher tell me that heavy lines were my ‘style’. They weren’t; I just hadn’t learned how to marry, blur or emphasize edges. These are technical skills, and to master them I had to move on to the Art Students League and teachers who understood the difference between technique and style.

Ultimately, we all end up with identifiable styles, but they should be un-self-conscious, the result of putting paint down many, many times. Anything that we do to avoid learning proper technique is not a style, it’s a failure.

Blues player Shakin Smith once told me that his style was the gap between his inner vision and his capacity to render it. That made me stop worrying about style at all.

|

| Vineyard, by Carol L. Douglas, courtesy of Kelpie Gallery. The dominant greens in this painting are based on ivory black. |

Don’t use black: “Monet didn’t use black, and you shouldn’t, either!” That’s true, but only after 1886, when Monet (apparently) adopted a limited palette. On the other hand, his palette included emerald green, which was copper-acetoarsenite, the killer pigment of the 19th century. There are limits to aping the masters of the past.

Monet made chromatic blacks, which are mixtures of hues that approximate black. Every artist should learn how to make neutrals, and not rely on buying Gamblin’s premix. But there are places where black is useful. One is in mixing greens. Another is in mixing skin tones. Contemporary painting is all about the tints (mixing with white) but ignores shades (mixing with black) and tones (mixing with black and white).

|

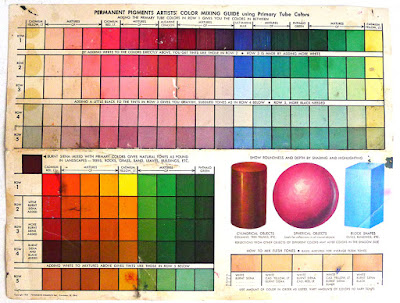

| Back in the day, art students learned not just tints, but shades and tones. |

Pros use more paint:Beginning artists generally don’t use enough paint, so it’s useful to tell them to increase the amount of paint. However, there are some great painters out there who work very thin—Colin Pageis an excellent example. The problem is in getting to that point. It’s a mastery born of years of experience. To get there you need—annoyingly—to start with more paint.

|

| Fish Beach, by Carol L. Douglas. |

If it’s not beautiful, you’re doing something wrong: Seeking beauty instead of truth is a great way to make static paintings. Paintings go through many ugly phases before they’re finished, and sublimating their ragged edges is a great way to drain all the juice out of your painting.

I’ve got one more workshop available this summer. Join me for Sea and Sky at Schoodic, August 5-10. We’re strictly limited to twelve, but there are still seats open.