We don’t control our legacy; we just do our best work and hope for the best. But, please, if you love me, don’t tell me you like my writing better than my painting.

|

| Pull up your Big Girl Panties, 6X8, is one of the paintings at Rye Arts Center this month. |

Next Thursday, I give a short talk at the opening of Censored and Poetic at the Rye Arts Center in New York. It will be livestreamed; you can register here. I’m no stranger to speaking; I generally lecture for 25 minutes each week to my painting classes. That takes me about three hours to research and write.

Cutting that in half increases the prep time exponentially. The more economical the text, the longer it takes to prepare. Certainly, the more emotionally engaged you are with the subject, the more difficult it is to put it in lucid order, and I’m passionate about my subject.

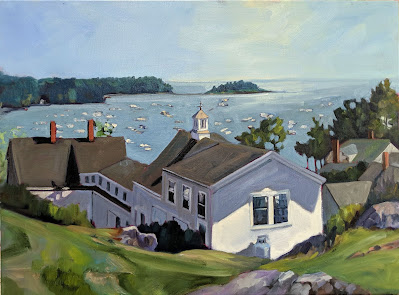

|

| Spring, 24X30, is one of the paintings at Rye Arts Center this month. |

The net result is that I’ve used my entire week writing and practicing my talk. I’ll get out tomorrow for a few hours of plein airpainting in the snow, but that’s only because I’m doing a photo shoot with Derek Hayes.

I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time recently writing. And yet, I don’t think of myself as a writer, but a painter. This winter, it seems, I’m a writer whose subject is painting. Or, perhaps I’m a painter who writes.

It’s all very annoying. I’ve spent many years learning the craft of painting and almost none learning to write. That comes as naturally to me as talking.

|

| Michelle Reading, 24X30, is one of the paintings at Rye Arts Center this month. |

All of us carry these labels. I told someone recently that my husband was a programmer. He corrected me, because he is—of course—a software engineer. Not being in the profession, I don’t understand the difference, but it clearly matters.

Labels can be limiting. Mid-century America used to talk about the ‘Renaissance man.’ This was a polymath, a person who was a virtuoso at many things. That’s very different from the pejorative ‘Jack of all trades and master of none’ that we sometimes use to describe a person who can’t light on any one thing and do it well.

Polymathy was, in fact, a characteristic of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. Gentlemen (and some ladies) were expected to speak multiple languages, pursue science as a passionate avocation, play musical instruments, and draw competently, all while fulfilling their roles as aristocrats and courtiers. Of course, that was only possible because a whole host of peons (that would be you and me) attended to their every need from birth.

|

| This Little Boat of Mine, 16X20, is one of the paintings at Rye Arts Center this month. |

Having to work and do your own laundry tends to cut into one’s leisure time. In fact, in America, we have an inversion of the historic distribution of leisure. Our elite are workaholics. Wealthy American men, in particular, work longer hours than poor men in our society and rich men in other countries.

This leaves no time to do other things. It also affects our overall culture, since culture is the byproduct of leisure. We used to love highbrow things like classical music and art because the well-educated had time to turn their hobbies into art. Today our culture is much earthier, for good or ill.

Loretta Lynn made a commercial in the 1970s which opened with, “Some people like my pies better than my singin’.” I remember that and her 1970 hit single, Coal Miner’s Daughter, and, sadly, nothing else of her three-time-Grammy-Award oeuvre.

We don’t control our legacy; we just do our best work and hope for the best. But, please, if you love me, don’t tell me you like my writing better than my painting.