Yes, there are bathrooms. We like to call them ‘heads’ on a boat

|

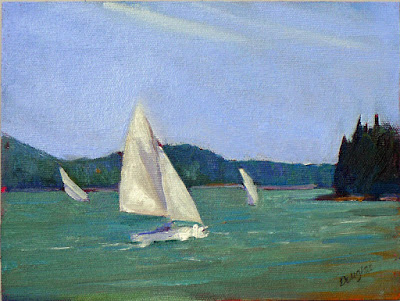

| Jonathan Submarining, by Carol L. Douglas |

If you’ve been thinking about taking my Sea & Skyor Age of Sailworkshops, this is a reminder that you have only two weeks left to get an early-bird discount. That’s $50 off the price of the boat trip or $100 off the Acadia workshop.

The

Age of Sail is June 10-14, 2018 on the historic schooner

American Eagle out of Rockland, ME.

Sea & Sky is August 5-10 at

Schoodic Institute in Acadia National Park. Here are some questions I’ve been asked recently:

|

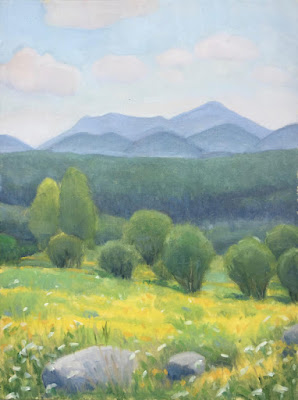

| Drying sails, by Carol L. Douglas |

What do you do if it rains?

While the rain in Maine falls mainly on the plain, it does sometimes rain over Penobscot Bay and the ocean. American Eagle has a canopy over the main deck for when the boat is at anchor, and we’ll use that. At Schoodic, we have access to a pavilion. In either case, if the worst happens and we’re totally unable to work outside, there are interior places where we can gather.

Are there bathrooms?

Yes and no. On a boat, a toilet is more properly called ‘the head.’ Although American Eagle is a restored heritage boat, she does have these modern conveniences. Schoodic Institute does, too.

On the boat, you’ll sleep in a berth. At Schoodic, you’ll have a room in an apartment with a kitchen, two bedrooms, two bathrooms, and access to laundry facilities. Out in the woods, we either drive to the nearest park facility, or we take an amble into the woods like the locals (bear, moose, and foxes) do.

|

|

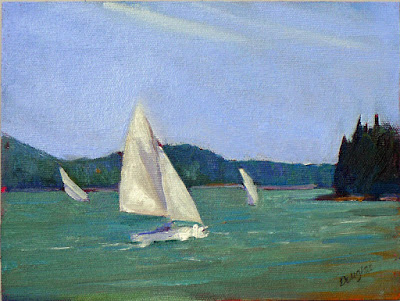

Outrunning the Storm, Carol L. Douglas

|

Are these workshops handicapped-access?

Schoodic Institute is, but let me know if you have physical limitations when you register. Our painting locations are all accessible by car and involve little hiking, so you won’t miss out. American Eagle is not accessible. It was built as a working fishing boat.

What about food?

In both cases, all meals are provided, so you don’t have to worry about where and when you eat. Schoodic’s chefs prepare lunches and snacks for us to take into the field, and we have breakfast and dinner cafeteria-style. American Eagle’s cook and mess-mate feed us three squares a day on deck.

Both trips include a lobster boil. Schoodic’s is prepared by a fisherman from nearby Corea, ME, who hauls that day’s catch over to us. On American Eagle, you’re likely to see Captain John Foss row his dinghy into a nearby harborage to buy seafood off the dock. You’re encouraged to make dinghy jokes.

|

| An island lobster bake, in progress. |

Can I get a glass of wine?

You can bring some along. In Maine wine and liquor are sold in grocery stores, and you can easily pick some up along the way.

What about black flies or mosquitoes?

I’ve painted in the far north from northern Alaska to Labrador, and the worst black flies I ever did see were at Piseco Lake in New York. They’re an early-summer phenomenon, which is why we’ll be out on the water in June and on land in August.

|

| Watercolor field sketches, by Carol L. Douglas |

What equipment should we bring?

For Sea & Sky, all mediums are welcome. Here are my packing lists for

oils,

acrylicsand

watercolor. The Age of Sail is a little different. I’m supplying everything, and we’re going to work in field-sketch style in watercolor and gouache, the better to capture fast impressions.

A reader once posted this comment on my blog: “Noted watercolor painter John Marin of the Maine coast not only painted many boats but also painted from a boat. He rowed out from Mt. Desert Island where he sketched and painted quick minutes-long watercolors while bobbing in his rowboat. One was on display at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art this past summer… Mount Desert Minute Drawing, most likely a view of Cadillac Mountain, and can be seen on

this web page.