Variation is your friend when you’re striving for movement in your painting.

|

|

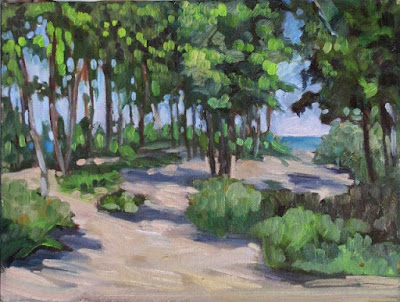

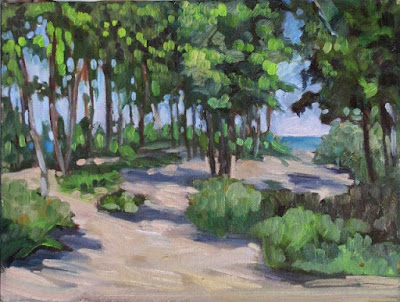

Beach Saplings, Carol L. Douglas

|

“You have a great sense of visual rhythm,” I told the young artist.

“I’m not sure I even know what that means,” he answered.

“Well, I’m not sure I do either, but I’m sure that between the two of us, we can figure it out,” I replied.

|

|

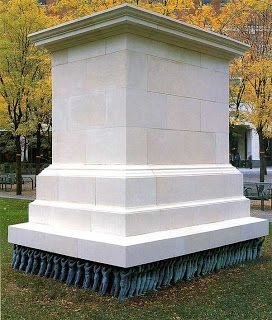

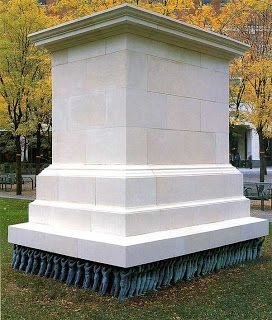

Public Figures, Do-Ho Suh 2001 Art Experience:NYC. The artist understood how to create movement enough that he intentionally suppresses it for a powerful political statement.

|

Rhythm creates visual tempo that provides a path for the viewer’s eye to follow. It’s closely aligned to movement and action, and it’s usually achieved through the repetition of lines, shapes and colors.

Rhythm builds on two other artistic concepts: Repetition, which is one object or shape repeated, and pattern, which is a combination of elements or shapes repeated in a recurring and regular arrangement. Rhythm is the song produced from these elements. It can be random, as in a pottery glaze, or obviously patterned.

The basic building block of rhythm is a motif. It need not be a real object. It can just as easily be an abstract shape.

|

|

Ejiri in Suruga Province, c. 1830, Katsushika Hokusai, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Ejiri in Suruga Province demonstrates the importance of motifs, rhythm and repetition in creating a sense of movement.

Katsushika Hokusai wanted us to understand that it was a very windy day. The blowing papers, the pattern of the grasses, the figures themselves and the doubled tree trunks are different motifs. They’re running across each other in different rhythms, giving an intense sense of motion to the foreground. This contrasts with the utter stillness of Mount Fuji in the background.

|

|

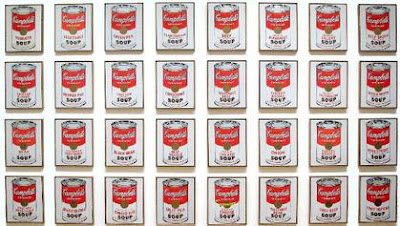

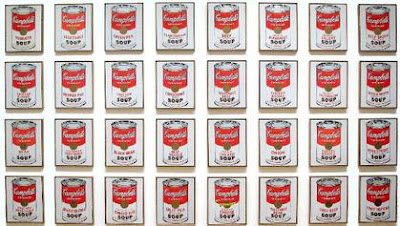

Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962, Andy Warhol, courtesy MoMA

|

Repetition can lift the prosaic into a new level, as Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans illustrate. Warhol went to his local grocery store and bought every flavor of soup Campbell was then making, 32 in all. Alone, one can of soup was meaningless; blocked together on shelves as at a grocery store, they created an immediately-recognizable symbol of the plentitude of American culture. (When asked why he painted soup cans, Warhol said, “I used to drink it, I used to have the same lunch every day, for twenty years.”)

|

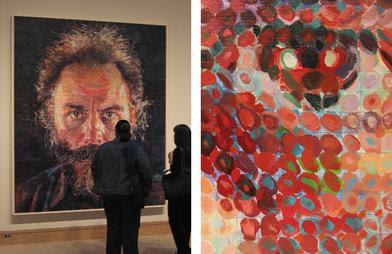

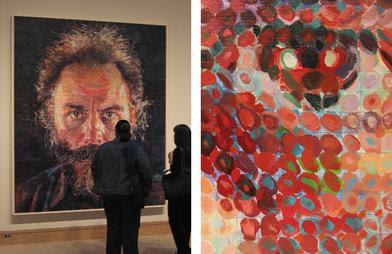

Lucas, 1986-87, by Chuck Close, fair use. His changing mark-making provides the only relief in these remarkably static portraits. |

The work of American painter

Chuck Close demonstrates the ability of rhythm to gin up an otherwise static painting. His first paintings were monumental monochrome hyperrealistic portraits. By the 1980s, he was superimposing a grid over them, breaking down the image into a series of dashes, dots, thumbprints, paper, or shapes. The pixelization gives them a degree of dynamism the earlier paintings don’t have.

How can you apply those principles of rhythm to your work?

|

|

Under the Marshall Point Light, Carol L. Douglas

|

Don’t be so quick to eliminate all evidence of the built world from your landscape paintings. Cars, telephone poles, houses and roads all create interesting visual patterns.

Be conscious of the rhythmic motifs in your subject before you start painting. Overlapping hills, granite outcroppings, tree patterns, and water ripples are all complex rhythmic patterns. Rhythm is a fundamental attribute of nature. Focus on it.

|

|

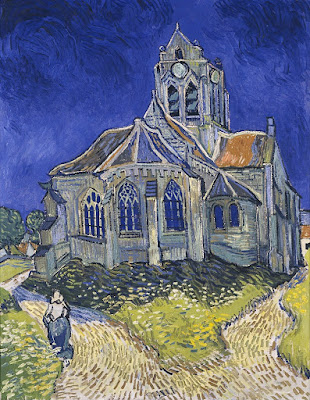

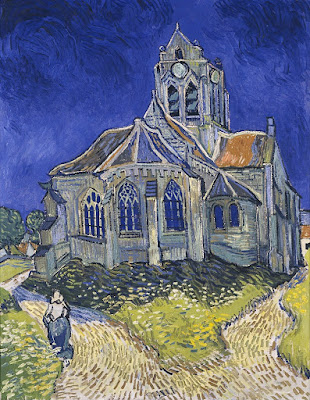

The Church in Auvers-sur-Oise, View from the Chevet, 1890, Vincent Van Gogh, Musée d’Orsay

|

Mark-making is an excellent way to insinuate rhythm into a painting. You can drive the viewer’s eye around your canvas by changing the thickness, length and direction of your strokes. The greatest practitioner of this was

Vincent van Gogh; study his work to see how you can apply this technique.

|

|

Children on the beach, 1910, Joaquín Sorolla, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

|

Color is a powerful tool for repeating motifs. See how

Joaquín Sorolla uses color temperature alone to make a pattern of ripples around his bathing children, above. Understand and use

color temperature.

Your assignment—should you choose to accept it—is to find and draw a naturally recurring motif in your immediate environment.