You’re nervous, wondering how on earth you got into this show in the first place. What now?

|

|

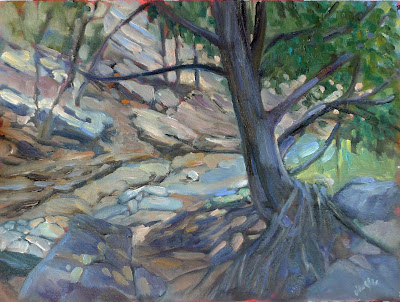

Brush Creek, by Jeanne Echternach, courtesy of the artist.

|

I’m holed up on a ranch east of the Pecos with six superlative painters here for

Santa Fe Plein Air Fiesta. “What advice would you give the emerging

plein air artist before his or her first big event?” I asked them.

“Find something that grabs you and not the thing you think is the most important thing to paint. If I don’t have that connection, then I don’t have that edge,” said

William Rogersof Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

|

|

Sonoran Preserve, by Richard Abraham, courtesy of the artist.

|

In other words, don’t focus on the picture postcard view. Sponsors often arrange paint outs for participating artists, and they’re very helpful to those who don’t know the area. But if it doesn’t move you, move on.

“When I was starting out, the worst thing was wasting time driving around looking for the best subject. Once you see something that would make a good painting, stop driving and start painting it,” said

Deborah McAllister of Lakewood, CO. “Don’t worry about the other painters in the event or whether you’re going to win an award or not.”

|

|

First Snows, First Light, by Karen Ann Hitt, courtesy of the artist.

|

It’s easy to be unnerved in what is, essentially, a competition. “Find the joy and don’t let the event get in your head,” cautioned

Jane Chapin of Santa Fe.

Remember that you were invited to this event because the jurors liked how you paint, so stop comparing yourself to others. That’s an insidious way to mess up your own excellent style. That doesn’t mean you can’t learn from others, but It’s best to put that in a tiny corner and ignore it for the duration of the event.

|

|

Ricardo and his horses, by William Rogers, courtesy of the artist.

|

I put the question to

Karen Ann Hitt, of Venice, FL, as she drove away merrily in her big truck. “Less talk and more wine,” I thought she said. Later, she told me she’d actually said, “Red wine and dark chocolate, main food groups!” I’ll take that to mean: remember to bring snacks and plenty of water.

Later, she talked about the first painting of the event. “Start small, keep it simple, and get your first one under your belt. Don’t sweat the details,” she said. It’s a trap to try to do your masterwork on the first run.

|

|

Vendor, by Jane Chapin, courtesy of the artist.

|

“Paint something you’re familiar with. Play to your strengths,” added

Jeanne Echternach, of Colorado.

Richard Abraham of Minneapolis knocked it out of the park with his first painting of this event. “Make sure you do your best painting the first day. Then you can relax,” he joked. But there’s some truth there. If your first painting is good, it builds confidence.

Still, you must leave room to be experimental. “Don’t chase your successes,” said Karen Hitt. By that, she meant, don’t fall into a formula. Take time to experiment, enjoy the place and the event, and challenge yourself.

|

|

Cottonwoods on the LaPoudre River, Deborah McAllister, courtesy of the artist.

|

“You can’t learn any younger,” said Jane Chapin.

Your painting will be better if you’re having fun. Take time to socialize. “Make friends with some new artists,” said Deborah McAllister.