Where do you fall on the continuum from representation to abstraction?

|

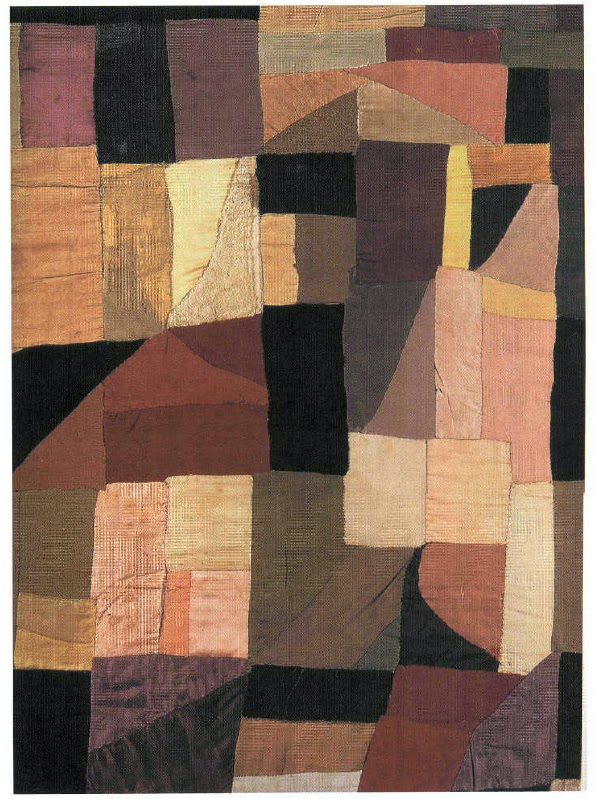

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928, Charles Demuth, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

English (my daughter never tires of telling me) is a descriptive, rather than proscriptive, language. Words mean whatever most people agree that they mean. That’s why English is so endlessly adaptable—why, for example, we can suddenly accept the ungrammatical ‘their’ as a replacement for ‘his’ or ‘her’ without making a Federal case of it. English sees a need and answers it, and its users follow along.

|

|

Rider, Attic red-figured cup, middle of 5th century BC, courtesy of Luynes Collection

|

Figurative is an old word in English, and comes to us from French. It has always had overtones of metaphor and meaning. It’s slightly different from figure, which has multiple meanings in English. Figurecan mean a shape, the human body; a number, or a symbol. Think of the term figure eight and you begin to understand the complexity of the word.

|

|

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, 1874, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, courtesy Detroit Institute of Arts

|

What is the difference between figurative and abstract art? It’s not easy to draw a line. There have always been elements of abstraction in figurative art. This is why ancient art often surprises us with its modernity.

|

|

Premier Disque, c. 1912-13, Robert Delaunay, private collection

|

The ‘figure’ in Charles Demuth’s I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold is both a number and a symbol. And it’s both abstract and realistic. It was painted in homage to his friend William Carlos Williams’ poem, The Great Figure:

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city.