We are affected by what has happened before us, and we have the power to influence those who follow.

| Blueberry Barrens, Clary Hill, will be at Camden Falls Gallery’s Autumn Hues show, opening this Thursday. |

I know a painter whose flawless technique is hitched to 19thcentury luminism. Another excellent painter watched him one day and sighed, “if he knew any art history, he’d be brilliant.” It was a sage comment. With a little understanding of modern art movements, my friend’s ability could be updated into something powerful, something that resonated with today’s viewers.

I’m not talking about putting on a new style like a shirt you bought at FatFace. That never works. Style is something that integrates one’s training, technique, emotional state, and personality. It’s what’s left when you’ve eliminated everything but inner truth. Done right, the artist has no more control over his or her style than he does over his autonomic nervous system. Try to put on an acquired style, and you’ll immediately be recognized as a poseur.

|

| Downdraft snow in the Pecos, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvas |

But note that I included training in that equation. To paint like a 19th century luminist today means ignoring the impact of a century and a half of war, the horrors of government-sponsored genocide, and the relentless push-pull of modern urban living. It means ignoring abstract-expressionism, magical realism, the invention of movies, color photography, and the entire digital age. There’s a reason modern painting has an edge that 19thcentury painting didn’t.

|

| Beach Erosion, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvasboard. |

With rare exceptions, my art-history posts are the least-read of anything on this blog. (I moved to this platform in 2007 and have my stats since then, with the exception of the period I was writing for the Bangor Daily News.) It’s always disappointing to write about a great artist of the past and realize nobody cares to read about him or her. But, like cod liver oil, I know art history is good for you, so I’m going to continue to offer it regularly.

None of us stand alone in the great continuum of history. We are affected by what has happened before us, and we have the power to influence those who follow. But to do that, to take our rightful places as painters or teachers, we need to be part of our epoch. To do that, we must understand where we are and where we came from.

| Tricky Mary in a Pea-Soup Fog, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvasboard |

That’s not limiting; it’s liberating. For example, observing how Bronzino painted energy into apparently-static portraits can make us better landscape or still-life painters. Our predecessors have experimented in color and composition in ways that can give us a firm foundation for our own exploration.

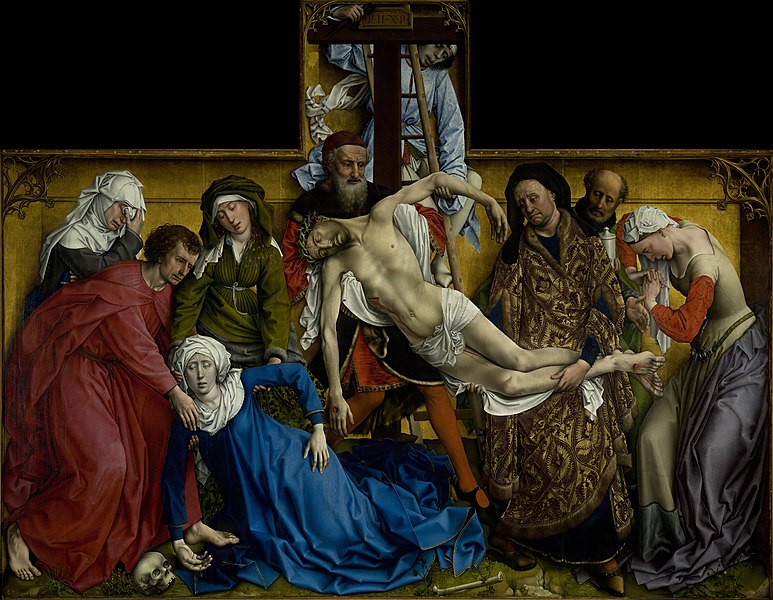

Understanding the goals of Rogier van der Weyden or Kazimir Malevich doesn’t make us paint like them. But understanding their place in the great sweep of time helps us to position ourselves in our place. Ultimately, that is the most important thing we learn through art history. It is the difference between a pretty painting and one that will have meaning to future generations.

.jpg)