Mature painters can apply for a residency at one of these great Maine art centers.

|

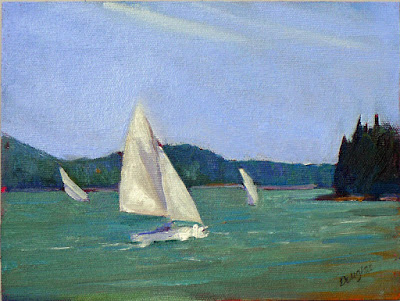

| Courtesy Hog Island |

This time of year, I can see the water of Rockport harbor from my bedroom window. I’ve been around the world, and I’m lucky to have landed in one of earth’s great beauty spots.

For those of you who dream about painting here, I’ve assembled a listing of visual artist residencies in the state of Maine. I have only included residencies that do not charge participating artists a fee. There are others, such as

Skowhegan’s summer program, that are wonderful but cost the artist money.

Bremen, ME

Applications due February 1, 2018

Residency Length: 2 weeks

Directed toward the artist whose work brings a broader appreciation of the natural environment, culture, and/or history of the coastal Maine ecosystem, and/or supports the mission of the Seabird Restoration Program to promote the conservation of seabirds and their critical habitats.

Applicants should be in good health and should be able to regularly walk the 6/10-mile uneven wooded path to the main campus for services. Expect solitude and immersion in nature, including varied weather and the possibility of ticks and mosquitoes.

At its nearest point, Hog Island is approximately ¼ mile from the mainland. Camp staff can ferry you back and forth if necessary. Residents who are comfortable with ocean navigation are welcome to bring a kayak and tie up at the cottages for their own transportation and at their own risk.

|

| Courtesy Haystack Mountain School of Crafts |

Deer Isle, ME

Open application starting January 1, 2018

Residency Length: May 27 – June 8

Haystack’s Open Studio Residency provides two weeks of studio time and an opportunity to work in a supportive community of makers. The program accommodates approximately 50 participants—from the craft field and other creative disciplines—who have uninterrupted time to work in six studios (ceramics, fiber, graphics, iron, metals, and wood) to develop ideas and experiment in various media. Participants can choose to work in one particular studio or move among them depending on the nature of their work. All of the studios are staffed by technicians who can assist with projects. Note: this is not a workshop and participants are expected to be technically proficient.

|

| Courtesy Hewnoaks Artist Colony |

Lovell, ME

Applications taken during the month of February, 2018

Residency Length: up to 2 weeks

Magnificently situated on the eastern shore of Kezar Lake, Hewnoaks offers an extraordinary setting of inspiration and beauty. By resurrecting its art-making traditions we aim to honor its creative history and preserve its environmental integrity.

Painters, sculptors, photographers, filmmakers, choreographers, actors, musicians, writers and curators are welcome. Preference is given to Maine artists. Artists are expected to work in their living space.

|

| Courtesy Maine Farmland Trust (Rolling Acres Farm) |

Jefferson, ME

Applications opened on December 1, 2017

Residency Length: 1 month/ 6 weeks

Residencies are for Maine artists, except for the Visual Arts program.

Six, month-long residencies: two in July, two in August and two in September, for visual artists. One placement is for an out-of-state or international artist, and one for a Maine artist.

One writing residency a minimum of four and maximum of six weeks long, July through mid-August. Applicants in the following categories can apply: Poetry, Prose, Fiction/Non-fiction.

One performing arts residency a minimum of four and maximum of six weeks long, during mid-August through end of September. Applicants in the following categories can apply: Performance/Dance, Storytelling, Songwriting.

Art & Agriculture- Seasonal Resident Gardener Position

This is a part-time, 5-month seasonal position for someone with at least 2 years of organic gardening experience and an affinity with the arts. The resident gardener will be living on-site with the visual arts and writing residents, and is encouraged to use their time at the Fiore Art Center for their own creative pursuits if desired.

|

| Courtesy Monhegan Artists’ Residency |

Mohegan, ME United States

Applications opened on February 1, 2018

Session length: 2/5 weeks

The Monhegan Artists’ Residency provides free comfortable living quarters, studio space, a stipend of $150 per week, and time for visual artists to reflect on, experiment, or develop their art while living in an artistically historic and beautiful location.

There are two 5-week sessions for artists with significant ties to Maine and one 2-week session for K-12 visual art teachers in Maine.

|

| Courtesy Schoodic Institute |

Winter Harbor, ME

Deadline: January 15, 2018

Session length: 2 weeks

In exchange for a two-week immersive experience, artists lead one outreach presentation with the public, and donate within one year one work of art that depicts a fresh and innovative new perspective of Acadia for park visitors.

Three categories of applicants are considered at present: Visual Artists; Writers; and At-Large Participants working in such forms as music composition, performing arts, indigenous arts, and emerging technologies. Applications are reviewed by appointed juries including park staff, community members, past program participants, and subject matter experts.

|

| Courtesy Tides Institute |

Tides Institute

Eastport ME

Deadline: February 1, 2018

Session length: 4/8 weeks

Founded in 2013 and now in its sixth year, The StudioWorks Artist-in-Residence Program at the Tides Institute & Museum of Art (TIMA) offers residency opportunities to visual artists from the U.S. and abroad to deepen and develop their practice within a community setting. The studios, museum and housing are located within the historic downtown and working waterfront of Eastport, Maine and overlook the U.S./Canada boundary.