They’re a feedback loop—speed creates confidence, and confidence in turn generates speed. Once you enter that loop, your painting will change very fast.

|

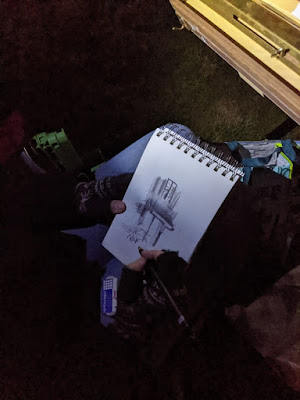

| From behind Rockefellar Hall, by student Carrie O’Brien (all photos courtesy of Jennifer Johnson, and I apologize for the color; they were taken indoors). |

The ferocious winds yesterday kicked the surf up and blew the last remaining clouds out to sea. Unfortunately, it also blew the last warmth away. It’s a chilly 42° out there this morning. However, the beauty of autumn is cold nights and warm days, and it will be sweater weather by the time we lift our brushes.

|

| From Frazer Point, by student Rebecca Bense. |

I have a location in mind for each day’s lesson; yesterday’s was to be the Mark Island overlook. This gives us a beautiful view of the Winter Harbor Lighthouse and the islands of Mount Desert Narrows. Unfortunately, it’s on the west side of the peninsula, backed by a mountain. The winds were roaring in from the northwest. Becky and Jean, who got there first, told us it was an untenable situation; something or someone was bound to be blown down the rocks.

|

| From Blueberry Hill, by student Ann Clowe. |

Instead, we sheltered in the leeward side of Rockefeller Hall, which is a massive faux-Tudor pile that houses Schoodic Institute’s offices. That gave us a shimmer of water through a screen of trees—a classic Canadian Group of Seven subject, and one that is ripe for personal interpretation. Lesser artists might look at that deceptively-simple screen of trees and lawn and decide there was nothing there. My students embraced the idea that they were certain timeless forms waiting to be rearranged in any order they chose.

|

| Surf by student Linda DeLorey. |

The greatest impediment to good, clean painting is flailing around—not having a well-thought-out plan, or not sticking to it. A consistent painting process not only gives you a bright, clean result, it also allows you to paint a good field sketch in three hours. That’s not important because you can churn out more paintings, but because the freshness of alla primapainting lies in its immediacy. I have several students in this class who are at that point already, and the rest are getting close.

|

| From Frazer Point, by student Beth Carr. |

Speed and confidence are a feedback loop—speed creates confidence, and confidence in turn generates speed. Once a student enters that feedback loop, his painting will change very fast. It is more important to concentrate on painting a lot than on painting perfectly, a point drilled home by David Bayles and Ted Orland in their classic Art & Fear: Observations On the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking.

|

| From Blueberry Hill, by student Jean Cole. |

Because these students have embraced process so avidly, we’ve been able to move beyond questions of paint application to more advanced issues like pictorial distance and the lost-and-found line. We’ve spent a lot of time working on clean traps and edges and avoiding mush. Today, we’ll be painting boats, which are the maritime equivalent of architecture.

And like that—boom!—another week at Schoodic is done. Dang.

|

| Jack pines by student Jennifer Johnson. |

After this, there’s Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air in Tallahassee, Florida, in early November. Today’s the deadline to register, but Natalia Andreevais painting in Apalachicola and has no signal, so you’ve got the weekend. After that, I have a few more plein air classes in Rockport, ME. From there on in, it’s all Zoom, Zoom, Zoom until the snow stops flying. For a year when nothing was happening, time has sure flown by.