If you say grace tomorrow, you could do worse than thanking God for the four freedoms enumerated by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

|

| Freedom from Want, 1943, Norman Rockwell |

I had a painting teacher who hated Norman Rockwell. She was in agreement with the art establishment of her time, which derided him as ‘just an illustrator.’ They also rebelled against his view of America, but that wasn’t what she said. “He has no sense of perspective,” she told me. “He just layers objects to give the illusion of depth.”

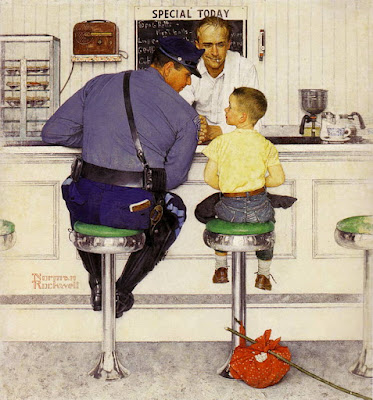

For some of his cover art that was true. Consider The Runaway (below), painted for the September 20, 1958 cover of the Saturday Evening Post. It’s just three figures square to the picture plane, surrounded by the horizontal lines and miscellany of the soda shop counter. If that was the only Rockwell painting you ever saw, you could be forgiven for thinking as she did.

|

| The Runaway, 1958, Norman Rockwell |

Compare that with Shiner (also below), from the May 23, 1953 cover of the same magazine. The little girl is again square to the picture plane, but there is a second focal point at the top right. They’re tied together by the linoleum. We’re seeing the subject from a kid-height viewpoint. Rockwell understood perspective quite well, thank you.

Freedom from Want was painted during World War II as part of Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series. The series was meant to illustrate a passage from President Franklin Roosevelt’s State of the Union address of January 6, 1941, when Nazi Germany occupied most of Western Europe. The paintings were so idiosyncratically American, however, that they instead have come to represent American values. Freedom from Want is now irrevocably entwined with the American holiday season, which kicks off tomorrow.

The foil for the whole painting is the white-on-white table, surrounded by a wreath of faces. If you’ve ever wondered about Rockwell as a painter, study that table. He’s as brilliant with the whites as Joaquín Sorolla, albeit in a much more American way.

|

| Shiner, 1953, Norman Rockwell |

The table is significantly foreshortened and the centerpiece—a fruit bowl—is at the very bottom of the picture. That and the truncated faces at the bottom make you wonder how much longer the table actually is.

This clever cropping make you think you’re looking at a snapshot of someone’s dinner. Of course, you’re not. He painted the figures from life, using his friends and neighbors as models. About the turkey, Rockwell said, “Our cook cooked it, I painted it and we ate it. That was one of the few times I’ve ever eaten the model.”

Note that there’s almost no other food on the table. Such is the magic of his realism that Rockwell makes you believe it’s an overloaded table. In fact, that was the criticism of it at the time, that it depicted indulgence while Europe was starving.

Of course, Thanksgiving is a meal of excess. (I myself plan to make seven pies today.) But if you say grace tomorrow—and I hope you do—you could do worse than thanking God for the four freedoms enumerated by President Roosevelt all those years ago:

Freedom of Speech

Freedom from Want

Freedom from Fear

Freedom of Worship

This was originally published in 2017. Have a very blessed holiday!