There’s science—okay, at least pop science—behind the idea that a bright white canvas will distort your painting.

|

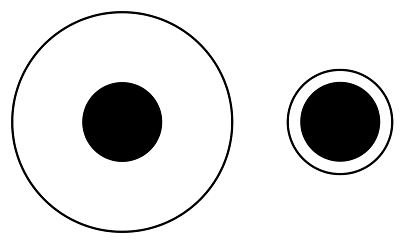

| One example of the Delboeuf Illusion, courtesy Wikipedia. |

“Why tone my canvases?” is perhaps the most common question oil-painting students ask me. It’s all about optical illusion. The size, shape and color of the objects we paint are influenced by their background.

The Delboeuf illusion is a distortion of relative size. In the illustration above, the two black disks are the same size, but one is surrounded by a tight ring; the other by open white space. The human eye sees the surrounded disk as larger than its non-surrounded twin.

The Delboeuf Illusion is in pop-science news these days because psychologists have found that people who eat meals served on smaller plates have a tendency to feel fuller faster. Oddly, animals also display food preferences based on plate size, but they don’t always correlate to our reactions. Dogs, for example, go for bigger plates. Dogs are such unwilling dieters.

|

| One example of the Ebbinghaus Illusion, courtesy of Wikipedia. |

Closely related is the Ebbinghaus Illusion, in which perception is influenced by the presence of nearby shapes. In the example above, the circle surrounded by a ring of large shapes appears smaller; that surrounded by a tighter ring of smaller shapes appears larger.

In both examples, if the shapes were all on a neutral-value ground, the contrast would disappear and the illusion would be broken.

Susceptibility to the Ebbinghaus Illusion is strongest in those with highly-developed visual cortexes (such as artists). It’s context dependent, so little children fall for it less often than adults. That would indicate that these visual cues are part of how we learn to navigate our environment. Relative size is a big clue to how far away an object is.

|

| Sarcone’s Cross Illusion, courtesy of Wikipedia. |

Sarcone’s Cross is an illusion that works in the opposite way. The cross dwarfed by large black squares appears larger, not smaller. The takeaway lesson for artists is that there isn’t an easy way to predict how the color and value of neighboring objects will influence what we next put down on paper or canvas. However, we can be sure that they will. This is why value studies are such an important part of painting design.

All of these optical illusions are explored in color in Josef Albers’ classic textbook, Interaction of Color. It may not be that much help on a practical level, but it’s great fun to think about.

|

| One of Josef Albers’ experience on space illusions, from Interaction of Color, courtesy Yale University Press. |

So, what does this have to do with toning? Toning is invaluable in the initial stages of a work because it changes how you perceive masses placed on the canvas. A toned canvas helps the painter establish a pleasing value structure.

There are many fine painters who don’t need a toned ground to produce a fine painting. If our reactions to these optical illusions are learned, then it’s possible to unlearn them (or at least learn to compensate for them). But why work that hard when a simple sweep of color on your canvas will save you a lot of work?

None of this pertains to watercolorists, of course. The white of their paper is part of the design, and that makes the illusions part of their magic.