Intimate knowledge is a spur to creativity, because it places facts at the disposal of your subconscious brain.

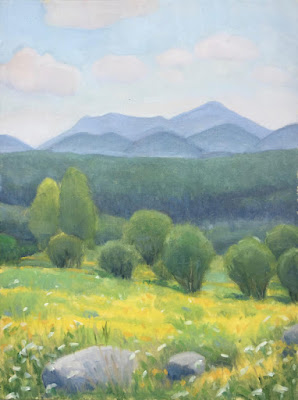

|

| Early Spring on Beech Hill, oil on canvasboard, Carol L. Douglas, 12X16, is available through the Camden Public Library. |

I’m in Boston waiting to board a plane. Logan International Airport bears scant resemblance to the historic city it serves (except for the inexplicable popularity of Dunkin’ Donuts). I can say that because I know Boston.

I’ve never been to Houston, but I will see it from the air since I have a layover there. I know it only by reputation: it’s big, new and southern.

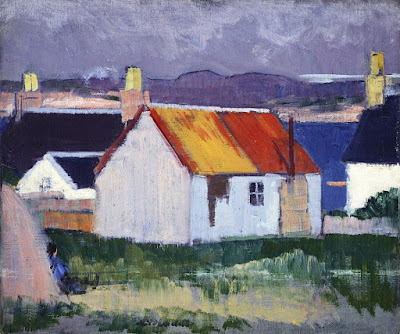

|

| Beauchamp Point, oil on canvasboard, Carol L. Douglas, 12X16, is available through the Camden Public Library. |

If I were to write a novel set in a contemporary city, which of these would be the sensible choice?

“Better if the country be real, and he has walked every foot of it and knows every milestone. As he studies it, relations will appear that he had not thought upon; he will discover obvious, though unexpected, short cuts and footprints for his messengers; and even when a map is not all the plot, it will be found to be a mine of suggestion,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson.

We’ve shortened that to the pithy statement “write what you know,” but that loses the point of Stevenson’s pronouncement. Intimate knowledge is a spur to creativity, because it places facts at the disposal of your subconscious brain. (It also stops you from making stupid mistakes, but that’s really the lesser consideration.)

|

| Home Port (Rockport), oil on canvasboard, Carol L. Douglas, 24X36, is available through the Camden Public Library. |

The same is true of painting. To paint well, you have to know your subject. When my show opened at the Picker Room of the Camden Public Library last Friday, my very first visitor asked me, “Are you from Maine?”

That’s a loaded question; it usually means “Were you born here, and your parents and grandparents, up to and including seven generations?” The answer, of course is, no—I’m from Buffalo and proud of it.

She was surprised. “You’ve caught the Maine of my childhood,” she said. “The real Maine.” I heard variations on that comment several times over the evening, enough that I started to consider what it meant.

|

| Clark’s Island, oil on canvasboard, Carol L. Douglas, 8X10, is available through the Camden Public Library. |

In Maine, people talk about ‘the dooryard.’ That’s a fine old term that’s fallen into disuse in the rest of America. It means that area around the door that everyone actually uses (which is not generally the front door). Paint Maine houses enough, and that dooryard emerges as something important. It doesn’t matter if you can articulate how or why you’re thinking about it; it will become a focus of your painting in a form louder than words.

That sort of truth-telling starts with careful observation, and observation in painting means drawing. We’ve somehow dropped that from our toolbox, but learning accurate drawing is the basis of all visual communication. It’s no different (or more difficult) than learning your times tables or how to sound out letters. And it’s just as basic and useful a skill.

“When my daughter was seven years old, she asked me one day what I did at work,” wrote artist Howard Ikemoto. “I told her I worked at the college—that my job was to teach people to draw. She stared at me, incredulous, and said, ‘You mean they forget?’”

I’m on my way to Mexico for a family wedding. I’ll be back on the weekend.